Whatness:

Pat Adams and Mariel Capanna in Conversation

Pat Adams, Uncoiling, 1980

Pat Adams, Uncoiling, 1980

Mariel Capanna: I read the transcript of the lecture you gave at Yale at Norfolk —now called Yale Norfolk School of Art. I worked there for the summer of 2019 — I was the program coordinator there. I was so happy to think that we have that place in common, that campus.

Pat Adams: I loved being there of course, I was lucky—they had Aldo Parisot’s cello studio that they let me paint in in the afternoons, because I was working as a secretary to the dean at the time.

You know we also have a shared relationship with Bob Schoelkopf — I saw that you have a grant with him. He and I met in 1952 in Florence, and the first modern painting that he bought was one of my 1952 works from my first show in Manhattan. So you and I go back 60 years! It’s really nice to have this nice part of the art world. So much of it is so crazy, but there really are deep affections that go on year after year through these different programs.

MC: I try as hard as I can to connect myself to the nice parts of the art world. I’m glad that we have some nice crossovers. And yes, I’ve not met Bob Schoelkopf, but I received the Schoelkopf Travel Award between my first and second years in graduate school and I used it to travel to the Cusco region of Peru to study Colonial-era wall paintings on plaster walls in churches and cathedrals. Not exactly frescoes — but kind of fresco-related paintings there. It was a pretty remarkable experience.

PA: I don’t know that material—it tends to be kind of flat, doesn’t it? The images are sort of boxed and set side by side in a flat way, or, how would you characterize what you saw?

MC: Well, the paintings that I saw in Peru were painted with earth and mineral pigments combined with a binder on dry plaster. I’ve spent some time studying true fresco painting, so I’m always interested in painting techniques that are related to fresco. The paint, materially, sits very flat on the surface—and in the case of these paintings in Cusco, there isn’t a lot of illusionistic depth; there’s a lot of flat imagery directly onto the wall. There’s also a fair amount of painting that emulates wallpaper. So there were different styles of painting in these spaces: sometimes the goal was more about storytelling, and other times it was more about decorative wall painting.

PA: I was sorry not to see the show at the Whitney of Orozco and those other fellows, but I read somewhere about the connection between the flatness of previous styles underlaid the flatness of Abstract Expressionism. They were saying that this was one of the things that Pollock and Rothko picked up, which is an interesting idea.

“Looking at your work, the early pieces that I saw, looking at the marks you were making I noticed that there were certain figurations. I wondered about that—were you concerned with timing between looking at and discovering things that were nameable?”

—Pat Adams

MC: Very much so. I’m sorry to have missed that show as well. Right now, I’m looking out on Lake Wesserunsett in central Maine. I’m on the campus of the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture where I’ve been working here this summer helping some alumni residents make fresco paintings in the barn. It’s a unique kind of painting because most paint materials are pigment plus some kind of binder, but in the case of true fresco, the binder is in the plaster on the wall, so it’s not until the pigment and the surface meet that the paint really forms.

PA: Looking at your work, the early pieces that I saw, looking at the marks you were making I noticed that there were certain figurations. I wondered about that—were you concerned with timing between looking at and discovering things that were nameable?

MC: That’s such a good question and I’ve thought a lot about “nameability.” I also saw that in some of your writing, this idea of “nameability” or “unnameability” came up. In my earlier paintings especially, the work is really an accumulation of nameable things. The titles of my paintings point to that as well—they’re usually some sequence of three to five nameable things you can find in those paintings. And usually the titles end up having a nursery rhyme-like rhythm, so they’re sounds and syllables as much as they’re words [describing the] things that are pictured. The nameable things end up being all of these little distractions that end up becoming an engine for shape and color and some kind of compositional structure. They’re usually gleaned from moving images, so I’ll watch some series of films or videos or slideshows and I’ll grab whatever it is that catches my attention and place it down. It often is as much a word as it is a color and shape. So, sometimes I’m noticing a shape of red in the upper left hand corner of the screen, but sometimes I’m remembering the word “car” or “hat.” So I’m naming things in the process of painting, but then they become an occasion for color and shape.

“I have a variation of that in my work. I call it quiddities, which means ‘whatness,’ which means it doesn’t have a name but it is a something. I, too, just grab things—whether it’s purple or anything else that comes in through whatever sense of mine I’m attending to. I feel very close to that idea.”

—Pat Adams

PA: In a way I understand what you’re saying and I have a variation of that in my work. I call it quiddities, which means “whatness,” which means it doesn’t have a name but it is a something. I, too, just grab things—whether it's purple or anything else that comes in through whatever sense of mine I’m attending to. I feel very close to that idea. I’m wondering what you’re thinking about as you have this diverse selection of things that you’re gathering together. Simultaneity in your mind is a good thing, yes?

MC: Yes, totally.

PA: When I think of simultaneity, it means that things are moving toward some kind of oneness.

MC: I’m so glad you’re mentioning this because this quality of all of the little disparate things and quiddities in your paintings and the feeling of wholeness and oneness is something I admire in your work and really aspire towards, so it’s been a really special pleasure to have this occasion to spend some time with some of your paintings.

PA: I have always used the word “multineity,” which is a made-up word in relation to simultaneity, because I’m always headed towards some sense of one—where everything all comes together rather than, say, where one style of art will try to diminish the qualities of the style that went before, and sort of piques a change of direction as a revolution. I myself don’t feel that at all—I look at what went before as having ideas that really relate to my sensibility, and I want to absorb them and bring them forward into some kind of great embrace.

“I have always used the word ‘multineity,’ which is a made-up word in relation to simultaneity, because I’m always headed towards some sense of one—where everything all comes together...”

—Pat Adams

MC: The other day, I woke up at 5:30 shortly after sunrise here and I decided to use the early morning to take a short jog that ended at a small beach here on campus that looks out onto the lake. Consistently in the morning here there’s this sheet of mist that pulls the water and the sky together into just one off-white color, and it really looks at first like a flat page. So I was on this beach looking at this seemingly opaque white, and then saw a reed sticking out of the water and then I saw its shadow, and then a heron flew by and also cast a shadow and that helped me see a pine tree in the distance, and then I saw the horizon line. All of these things were there—and then I could see thousands of minnows swimming by, and it was very quiet.

It did remind me a bit of what I’ve experienced in looking at your paintings. There’s this kind of vibration back and forth between seeing the embrace of the whole thing and then also these shimmering little parts that are very different from one other but also part of its whole. Something that I noticed this morning at the lake was this feeling that every movement that I made was so loud in the midst of this quiet misty morning, and I felt really aware of my ability to disturb the whole thing and throw it off.

This is something I’ve also been feeling in my studio more than usual—an overactive awareness of how a mark that I make can throw off some potential of wholeness. I’ve been thinking about some of your writing, about the ways in which a painting can become limited or constrained. I wonder if you ever feel hesitant about making a mark when you paint?

PA: Oh, constantly! I easily have about twenty or so works on paper up on a wall and I work from one to the other, one to the other, because it’s as if I’m waiting for the painting to tell me what it demands. [Creating these works can] take a couple of years.

“We stand in front of the emptiness and things just start to become visible, where one leads to another.”

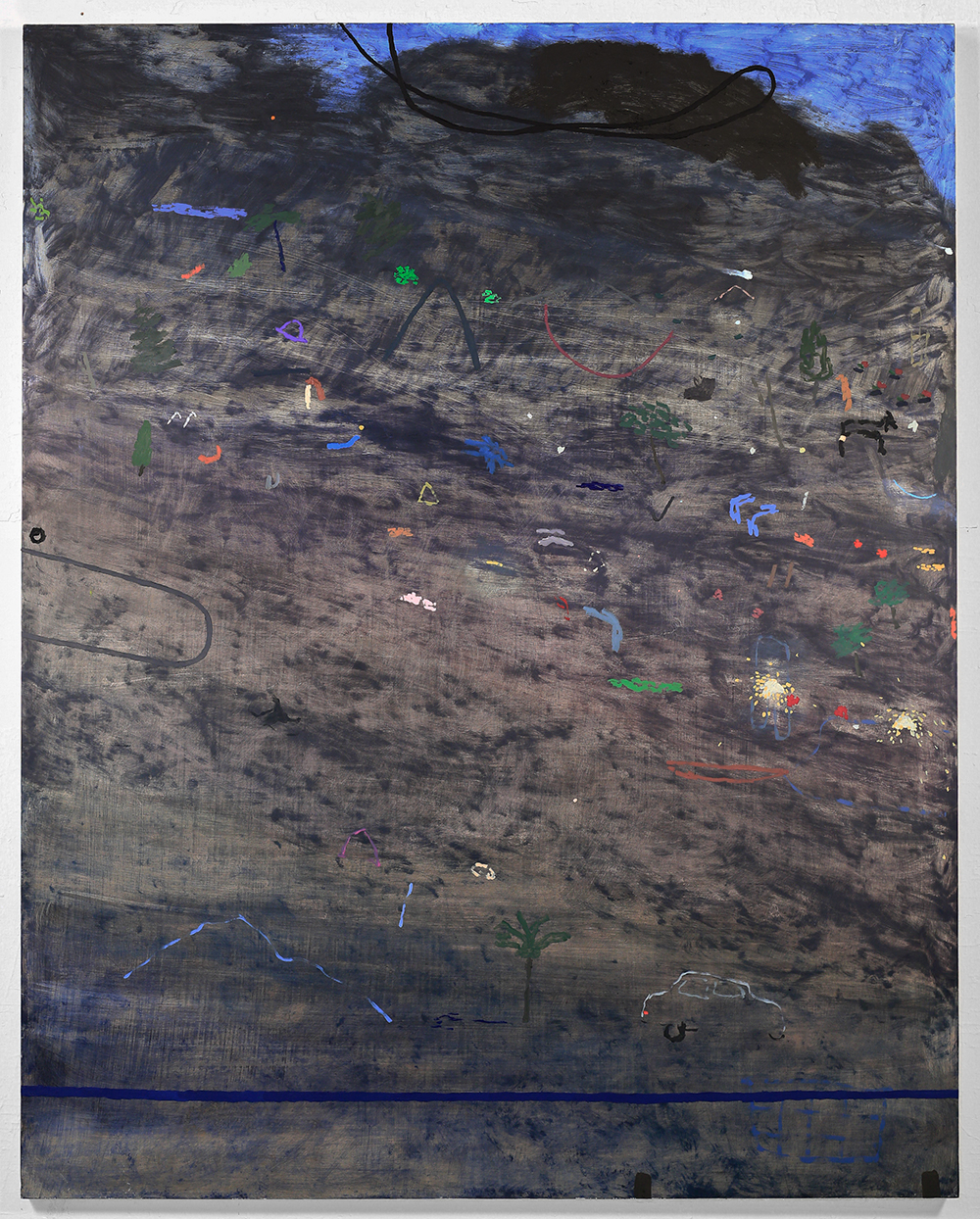

![]() Mariel Capanna, Fireworks, Billy Goat, Meteors, Shoe, 2021

Mariel Capanna, Fireworks, Billy Goat, Meteors, Shoe, 2021

I will say I love your description of your experience on the water that early morning, because what you said is really just like painting, isn’t it? We stand in front of the emptiness and things just start to become visible, where one leads to another. It is splendid to hear you speak about how you can acknowledge your own experience. This is the thing that bothers me terribly about the art world right now: artists are not really attached to themselves. They seem to be pushed around by whatever the world is doing around them, rather than spending time registering what one’s own inner direction is asking for. And to hear you talk about things this way is very encouraging to know that these things go on a little bit—thank you for that.

MC: Wow! I’m sure in many ways I’m also affected by whatever patterns you’re noticing—reactionary patterns. I do try to return to my sensory experience because it really is the thing that brought me to painting in the first place. I need to remind myself of that and learn and relearn that that is why I’m here and what I want to be doing. Your work and your writings are one of the things this summer that reminded me of where I want to be.

PA: I want to mention one of your paintings that was a crowd where suddenly the foreground has a large shape—and I love the fact that the color seems to be one of these marvelous kinds of transparent tints that doesn’t really have a name—it's almost tan-pink. But the shape of it in the foreground in relation to the continuation of the kind of activity that you’ve been marking all along I just thought was really just a terrific shift in emphasis. The amount of the undifferentiated surface of the figure is really a delight, I was quite taken with that.

MC: I would say that that work is, at this point, the only one of its kind, and maybe a new direction for me.

PA: I don’t want to disrupt where you’re going, but that kind of a commentary on your own direction is exciting.

MC: This one in particular is an example of where I’m kind of combining the logic of fresco painting with oil painting. The way that the work is structured is based on giornata lines which you were describing earlier—the delineated area of plaster where one day of work ends and the next begins. When you look closely at a fresco you can usually see the edge of the arm or a tree, a seam where two days of plaster meet. Here, I kind of imagined two giornata lines of two very different days of work and treated each day entirely differently.

PA: I love the intensity of the opposition.

MC: I’ve been feeling curious about the fact that all of the paintings in my studio right now seem to have entirely different color worlds from one another, and there was something confusing about that. I was looking through your paintings again today, and I saw how rich the world of color is in each one and also just so different from painting to painting. There really is a huge variance in color and saturation in your work. I wonder how you happen upon each of those distinct color worlds. Are those things that you gather outside of your studio?

PA: I think a lot of what I do is intellectual, in a sense. I read that Titian at one point said something about wanting no color—and I identified with that because at a point red, yellow, and blue just became appalling to me. It just looked like store paint or something, I couldn’t really bear it. I read somewhere else that he would glaze forty or sixty times over an area to bring it to the point that he wanted. I was very moved by those two statements—they fed into how I think about doing things.

MC: The slow build-up of color over time?

PA: Over time, or the rejection of just squeezing something out of a tube and thinking that color is green. I just find painting is such an incredible way of celebrating the richness of sensation. We really could have such a good time as an artist if we just added up all the greens that are outside the window. Maybe my sense of pleasure is bizarre, but I wish people had a little time to enjoy existence.

MC: I thank you for this very refreshing reminder. I arrived at painting—not exactly considered late in life—but I was an undergraduate at McGill University in Montreal and I was almost debilitatingly stuck in my head. I was studying mostly the sciences and was not doing any kind of work within the realm of art. My dad very generously recommended a semester off, which I hadn’t realized was a possibility. During that time off I took a drawing class at the Pennsylvania Academy for the Fine Arts where we were working [from observation of] plaster casts. I just remember that it felt like pleasure was possible again because of the connection to my senses. As long as there were shapes and colors and light and shadow around me, there was always going to be something worth noticing and considering. I’m long-windedly agreeing with you that painting is a pleasure! Thank goodness for that.

“As long as there were shapes and colors and light and shadow around me, there was always going to be something worth noticing and considering.”

PA: Do you do any teaching?

MC: I’m teaching now at Skowhegan but it’s very technical—I’m teaching the materials and techniques of fresco painting. And then I’m starting a two-year fellowship at Williams College.

PA: That’s a very interesting school. I’ll tell you, I taught drawing for about 20 years and what I loved about it was the utter silence and focus. In Bennington where I taught, next door was the theater and there would often be someone playing the flute or oboe and there would be this gallic sound just moving slowly through the space. Things like that you cannot replace—it’s a memory and a feeling that I treasure.

MC: My dad was the executive director of a community music school in Philadelphia called Settlement Music School. Growing up I would get dropped off after school at the music school. So that ambient sound of practice is a fond memory for me too.

PA: I think that dance and music are very important for painters to feel all the senses that make up the body. Music is a kind of refinement of the circumstances that we live in.

MC: A couple of weeks ago I was working with this painter at Skowhegan. Often in these fresco workshops that I run, people will kind of dive right into the surface and paint onto the plaster very quickly with a strong hand which can actually really disrupt the surface which is very delicate. This painter was sitting at the table with these three fresco panels in front of her and she sat for many minutes quietly, and it reminded me so much of someone doing the right thing before a piano performance — just taking the time to look and listen and wait. I have all of these fond memories of going to the music school, but I also remember that I had that problem that you might be familiar with — when I was in front of an audience, instead of trusting that my fingers knew what they were doing, I would tell them what to do.

PA: I always feel there’s a little bit of a battle between our distant affects, and I think the mind is absolutely wonderful but sometimes it can be too dominant and it can displace all the other things that our spirit is made up of. I thought it was interesting about the woman who is a gymnast [Simone Biles] who really was accepting that her body was out of sync with what she wanted to do. She recognized herself as not having the concentration that such a program would require. It’s a good lesson that we all need to attend to.

MC: Sometimes waiting is the right thing to do.

PA: It is.

Well, my mind is still on the beach with the mist binding the sky and water. It is a wonderful, wonderful image. My husband, who is gone now, and I went up behind us -- there was a college and a place where you could overlook the green mountains. The moon is a big event in my house because it comes right over the house. We wanted to go up there and watch the moon, because we knew it was going to be full, come about. We were up there and I’m still trying to deal with it because the color was a lavender graphite sky and the intimation of a pale, pale yellow before the edge of the moon appeared. I mean, it was really magical. I mean you really will need to get someone to drive you up there and have a look -- it is somewhat similar but at a different time of day.

Mariel, I look forward to talking to you soon again!

MC: You too, talk to you soon, Pat. Thank you for taking the time.

It did remind me a bit of what I’ve experienced in looking at your paintings. There’s this kind of vibration back and forth between seeing the embrace of the whole thing and then also these shimmering little parts that are very different from one other but also part of its whole. Something that I noticed this morning at the lake was this feeling that every movement that I made was so loud in the midst of this quiet misty morning, and I felt really aware of my ability to disturb the whole thing and throw it off.

This is something I’ve also been feeling in my studio more than usual—an overactive awareness of how a mark that I make can throw off some potential of wholeness. I’ve been thinking about some of your writing, about the ways in which a painting can become limited or constrained. I wonder if you ever feel hesitant about making a mark when you paint?

PA: Oh, constantly! I easily have about twenty or so works on paper up on a wall and I work from one to the other, one to the other, because it’s as if I’m waiting for the painting to tell me what it demands. [Creating these works can] take a couple of years.

“We stand in front of the emptiness and things just start to become visible, where one leads to another.”

—Pat Adams

Mariel Capanna, Fireworks, Billy Goat, Meteors, Shoe, 2021

Mariel Capanna, Fireworks, Billy Goat, Meteors, Shoe, 2021

I will say I love your description of your experience on the water that early morning, because what you said is really just like painting, isn’t it? We stand in front of the emptiness and things just start to become visible, where one leads to another. It is splendid to hear you speak about how you can acknowledge your own experience. This is the thing that bothers me terribly about the art world right now: artists are not really attached to themselves. They seem to be pushed around by whatever the world is doing around them, rather than spending time registering what one’s own inner direction is asking for. And to hear you talk about things this way is very encouraging to know that these things go on a little bit—thank you for that.

MC: Wow! I’m sure in many ways I’m also affected by whatever patterns you’re noticing—reactionary patterns. I do try to return to my sensory experience because it really is the thing that brought me to painting in the first place. I need to remind myself of that and learn and relearn that that is why I’m here and what I want to be doing. Your work and your writings are one of the things this summer that reminded me of where I want to be.

PA: I want to mention one of your paintings that was a crowd where suddenly the foreground has a large shape—and I love the fact that the color seems to be one of these marvelous kinds of transparent tints that doesn’t really have a name—it's almost tan-pink. But the shape of it in the foreground in relation to the continuation of the kind of activity that you’ve been marking all along I just thought was really just a terrific shift in emphasis. The amount of the undifferentiated surface of the figure is really a delight, I was quite taken with that.

MC: I would say that that work is, at this point, the only one of its kind, and maybe a new direction for me.

PA: I don’t want to disrupt where you’re going, but that kind of a commentary on your own direction is exciting.

MC: This one in particular is an example of where I’m kind of combining the logic of fresco painting with oil painting. The way that the work is structured is based on giornata lines which you were describing earlier—the delineated area of plaster where one day of work ends and the next begins. When you look closely at a fresco you can usually see the edge of the arm or a tree, a seam where two days of plaster meet. Here, I kind of imagined two giornata lines of two very different days of work and treated each day entirely differently.

PA: I love the intensity of the opposition.

MC: I’ve been feeling curious about the fact that all of the paintings in my studio right now seem to have entirely different color worlds from one another, and there was something confusing about that. I was looking through your paintings again today, and I saw how rich the world of color is in each one and also just so different from painting to painting. There really is a huge variance in color and saturation in your work. I wonder how you happen upon each of those distinct color worlds. Are those things that you gather outside of your studio?

PA: I think a lot of what I do is intellectual, in a sense. I read that Titian at one point said something about wanting no color—and I identified with that because at a point red, yellow, and blue just became appalling to me. It just looked like store paint or something, I couldn’t really bear it. I read somewhere else that he would glaze forty or sixty times over an area to bring it to the point that he wanted. I was very moved by those two statements—they fed into how I think about doing things.

MC: The slow build-up of color over time?

PA: Over time, or the rejection of just squeezing something out of a tube and thinking that color is green. I just find painting is such an incredible way of celebrating the richness of sensation. We really could have such a good time as an artist if we just added up all the greens that are outside the window. Maybe my sense of pleasure is bizarre, but I wish people had a little time to enjoy existence.

MC: I thank you for this very refreshing reminder. I arrived at painting—not exactly considered late in life—but I was an undergraduate at McGill University in Montreal and I was almost debilitatingly stuck in my head. I was studying mostly the sciences and was not doing any kind of work within the realm of art. My dad very generously recommended a semester off, which I hadn’t realized was a possibility. During that time off I took a drawing class at the Pennsylvania Academy for the Fine Arts where we were working [from observation of] plaster casts. I just remember that it felt like pleasure was possible again because of the connection to my senses. As long as there were shapes and colors and light and shadow around me, there was always going to be something worth noticing and considering. I’m long-windedly agreeing with you that painting is a pleasure! Thank goodness for that.

“As long as there were shapes and colors and light and shadow around me, there was always going to be something worth noticing and considering.”

—Mariel Capanna

PA: Do you do any teaching?

MC: I’m teaching now at Skowhegan but it’s very technical—I’m teaching the materials and techniques of fresco painting. And then I’m starting a two-year fellowship at Williams College.

PA: That’s a very interesting school. I’ll tell you, I taught drawing for about 20 years and what I loved about it was the utter silence and focus. In Bennington where I taught, next door was the theater and there would often be someone playing the flute or oboe and there would be this gallic sound just moving slowly through the space. Things like that you cannot replace—it’s a memory and a feeling that I treasure.

MC: My dad was the executive director of a community music school in Philadelphia called Settlement Music School. Growing up I would get dropped off after school at the music school. So that ambient sound of practice is a fond memory for me too.

PA: I think that dance and music are very important for painters to feel all the senses that make up the body. Music is a kind of refinement of the circumstances that we live in.

MC: A couple of weeks ago I was working with this painter at Skowhegan. Often in these fresco workshops that I run, people will kind of dive right into the surface and paint onto the plaster very quickly with a strong hand which can actually really disrupt the surface which is very delicate. This painter was sitting at the table with these three fresco panels in front of her and she sat for many minutes quietly, and it reminded me so much of someone doing the right thing before a piano performance — just taking the time to look and listen and wait. I have all of these fond memories of going to the music school, but I also remember that I had that problem that you might be familiar with — when I was in front of an audience, instead of trusting that my fingers knew what they were doing, I would tell them what to do.

PA: I always feel there’s a little bit of a battle between our distant affects, and I think the mind is absolutely wonderful but sometimes it can be too dominant and it can displace all the other things that our spirit is made up of. I thought it was interesting about the woman who is a gymnast [Simone Biles] who really was accepting that her body was out of sync with what she wanted to do. She recognized herself as not having the concentration that such a program would require. It’s a good lesson that we all need to attend to.

MC: Sometimes waiting is the right thing to do.

PA: It is.

Well, my mind is still on the beach with the mist binding the sky and water. It is a wonderful, wonderful image. My husband, who is gone now, and I went up behind us -- there was a college and a place where you could overlook the green mountains. The moon is a big event in my house because it comes right over the house. We wanted to go up there and watch the moon, because we knew it was going to be full, come about. We were up there and I’m still trying to deal with it because the color was a lavender graphite sky and the intimation of a pale, pale yellow before the edge of the moon appeared. I mean, it was really magical. I mean you really will need to get someone to drive you up there and have a look -- it is somewhat similar but at a different time of day.

Mariel, I look forward to talking to you soon again!

MC: You too, talk to you soon, Pat. Thank you for taking the time.