Stefanie Victor

September 18–October 30, 2021

Jenelle Porter in coversation with Stefanie Victor

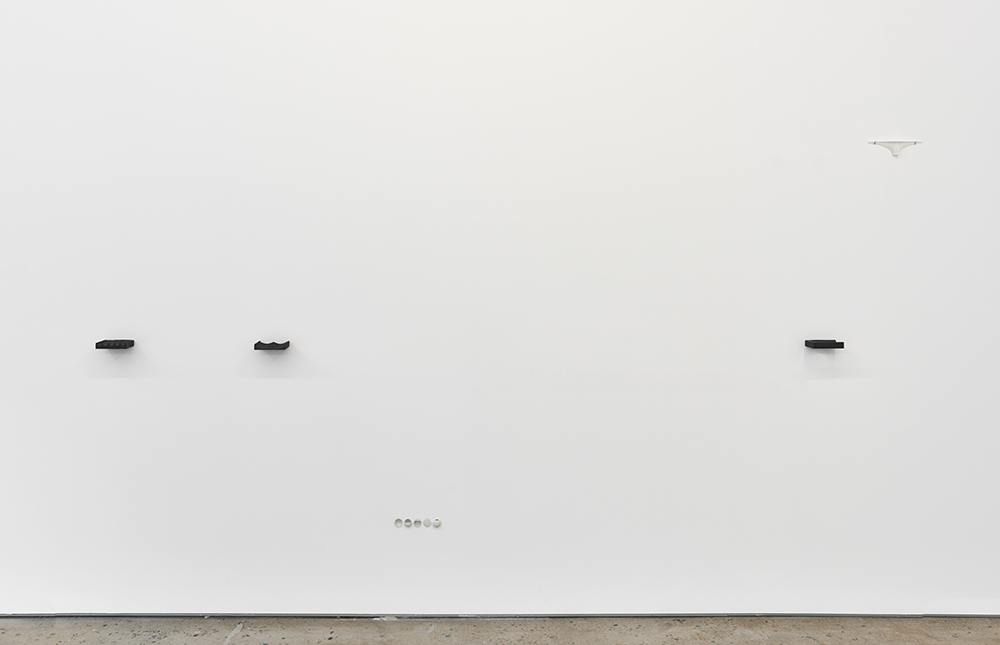

Adams and Ollman is pleased to announce a solo exhibition of new work by Stefanie Victor. For this exhibition, the artist’s second at the gallery, Victor explores gesture and form as it relates to her affective experience with domestic objects, space, time, and studio processes through six different types of works installed in subtle spatial rhythms around the gallery. In doing so, Victor investigates the capacity for discrete elements to collectively map a kind of language of private experience. The exhibition opens on September 18 and is on view through October 31.

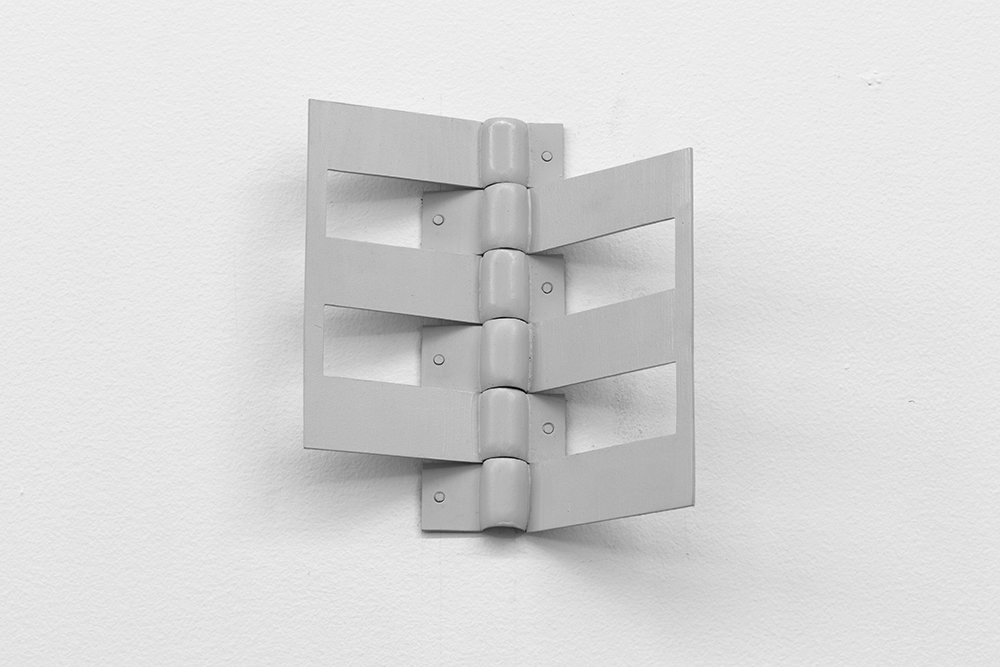

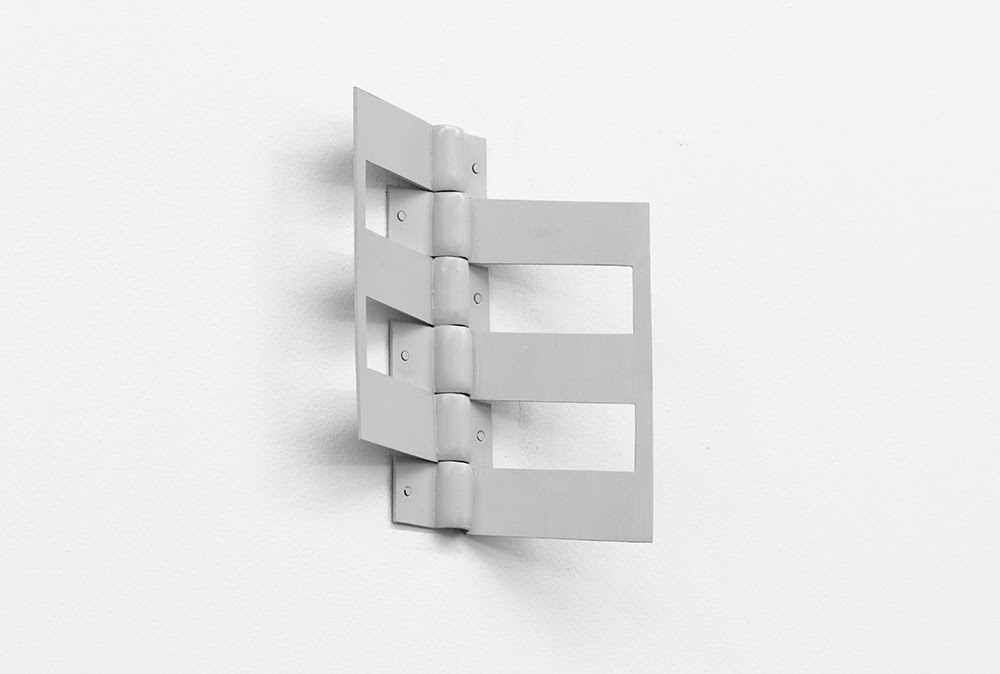

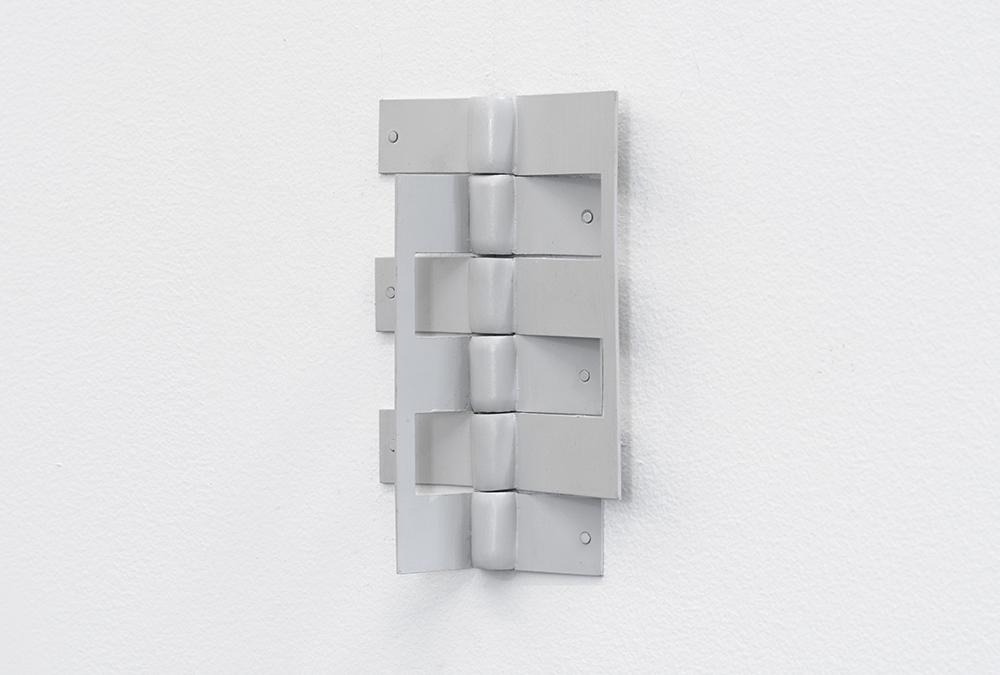

Small in scale and carefully adapted to the gallery space, the sculptures relate to the body and its movements, as well as interior infrastructure and hardware in Victor’s apartment. Made from a range of raw materials including cement, glass, metal, and clay, their forms often belie their materiality. Rather than hard and still, they conjure the possibility of pliancy or activation. Recurring, shifting, and singular elements suggesting and disrupting pattern, reference the repetition of commonplace elements such as hinges, decorative moulding, and electrical cords. But the sculptures’ abstract qualities, unusual relationships to the wall, unexpected details, slight variations, and imperfections borne from hand-made processes shift the work away from the mechanized and familiar and towards more particular, human kinds of forms.

As in past work, Victor foregrounds intimacy and incorporates the confines of the body, studio, and home to create meaning that exists first of all in private, performed and made for no one but the artist herself. The works on view are a distillation of time spent in the studio turning, bending, moving, shaping, pushing, and folding. Accrued gestures from routine domestic movements such as closing a door, drawer or window, opening the blinds, turning on the lights, or plugging and unplugging cords, surround and find expression in her practice and this work. The sculptures quietly imply their own abstract uses, and gesture back to unseen movements as once malleable materials formed and re-formed by hands now absent.

Also on view in the small room will be a series of works on paper by Victor that complements the installation.

Stefanie Victor was born in 1982 and lives and works in Queens, New York. She earned a MFA in Painting from Yale School of Art in 2009, and a BFA in Printmaking from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2004. Her work has been included in exhibitions at MoMA PS1, New York; Participant, Inc, New York; and the Drawing Center, New York, among others.

Works

Stefanie Victor

Untitled, 2021

glass and nickel; cement and graphite; glazed porcelain; painted brass; brass; painted copper and bronze

set of 14 sculptures

dimensions variable

SVic2021001

Stefanie Victor

Untitled (Gesture Drawings), 2018

silkscreen and relief

35h x 67 1/2w in

88.90h x 171.45w cm

SVic2018007

In collaboration with Marginal Editions

Details and Installation Views

In Conversation:

Jenelle Porter and Stefanie Victor

Jenelle Porter: Today is August 6, 2020. We’re conducting this interview during a pandemic, via a new feature in our lives, the video conference call. I’m in Los Angeles and you’re at home in Queens. What are you making now?

Stefanie Victor: I’m working on whatever I can for the upcoming exhibition, but much of the production is paused. But what I’m making now is a body of work I’ve had in mind for about two years, which essentially extends my work from individual objects to groups of objects that repeat or vary, and create spatial rhythms around the room. There will be four components and they’re currently in various stages of completion. So, I started working on another little project that is not close to being ready for the world and feels like something that probably wouldn’t have happened if we weren’t sheltered in our home the way we are. I’m looking at the soap dish in my bathroom, which has these indentations that grip the soap but are also ornamental.

JP: Is it the kind of ceramic soap dish that’s tiled onto the wall?

SV: Exactly. It’s embedded in the infrastructure, if I can call it that. I’m thinking about them like a series of horizontal paintings or little horizontal friezes.

JP: So you’re looking at the objects around you, in your home. This isn’t such a departure from the way you work, right?

SV: That’s true, but it feels somehow both especially apt and especially absurd now. I’m spending so much time in my apartment, looking even more at my interior space, while there’s so much happening outside that’s vastly more important, and bigger, and heavier than I can really comprehend.

JP: We’re all hand washing and handwringing.

SV: The soap dish is really mundane, just a little part of my home, but it’s led to some new ideas.

JP: Is your studio in your home?

SV: Yes. I’ve always worked at home, except for when I was in grad school. I’ve taught high school for the past ten years, and so just on a very basic, day-to-day life habit, having the ability to get out of bed on Saturday, work on something for forty-five minutes, run an errand and then do some more work, has always felt right for me. I’m not the kind of artist that goes at a painting for eight hours at a stretch. And I have a son, so, you know, I can make him a sandwich and then he gets absorbed in his Legos and I can go in and work.

JP: I’ve been thinking about artists working at home, for so many pandemic-related reasons, but also because I’m writing about Ruth Asawa, an artist whose art and life were so consciously intertwined. She made her art at home, alongside her roles as a mother, wife, friend, activist, and teacher. I think many of us have bought into a fantasy of what a so-called working artist looks like, that there’s one “right” way to fulfill that role, yet we recognize that fantasy is based on a white, hetero, male, Western canon. But this idea of domestic space in your work, this idea of working as one can, when one can, is typically gendered female. You’ve made several bodies of work named for women artists. Would you talk through some of those? Perhaps begin with the Geta series?

SV: I came across Geta Brătescu’s work in a collection show at MoMA [Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2016], these smallish textile works that were really striking and beautiful [Medea’s Hypostases series, 1980, drawing with sewing machine on textile]. I’ve always been interested in fabric and textile art, which is probably why I looked her up later. I discovered this quite wide-ranging body of work that, to be honest, I just connected with on a visual level. I got books on her work, and I looked at the pictures before I read anything. I came across this film called Hands (For the Eye, the Hand of My Body Draws My Portrait) [1977, black-and-white silent film, 7:30 minutes]. It’s an overhead shot of her hands at her desk in her studio. And one of the first things that crossed my mind was how similar it was to some videos that I’d tried to make a couple of years earlier. My work is small and I’m working with my hands, and working with everyday objects at least to make forms and shapes and models. This isn’t to say that I think her work, which is coming from a particular place and time, is coming from the same place I am. But I’m looking at it, and thinking, this is me. Or, this feels like the under layer of my process, the circling of the hands, the mapping of her bones with a marker, the twisting of things and throwing things out. Her film is a bit more theatrical, but it felt like this kind of connection through process. My work doesn’t scream process; it’s quiet and finished in ways that you don’t really see my hand. So in a sense naming my work “for Geta” felt like a way to connect through the work behind the work. It also felt like license to pursue forms that directly come from the body, and the hand and eye in particular.

JP: And in any sense did her way of working give you a feeling of confirmation?

SV: Yes, totally. It’s like when you’re reading a book and the author has an insight into a thought process that you didn’t even know you were having.

![]()

Stefanie Victor with Geta Brătescu, installation view, Adams and Ollman, 2018.

JP: I know exactly what you mean. I have that feeling all the time when I read fiction. It’s like a transmission through time and space, a confirmation that there is a kind of timelessness or an energy that threads through our bodies. I think it can be incredibly moving to linger in that sensation of universality.

I try not to make things unless I really want to make them. I don't make a lot of stuff, you know, and I feel there is an economy to what I make. I have to have a pretty strong desire to try something, and then I just try to rely on that feeling.

SV: Especially right now as we’re all experiencing some kind of loss of connection. The artists that I’ve responded to the most don’t know me, but I think this kind of connection gives me a stronger ground on which to stand. I think that there’s something that can be isolating about making art. I think it’s hard to justify making visual art. You know, when there’s so many other ways you can use your time, but if I didn’t feel those relationships to other artists, I would feel lost.

JP: Those connections are a kind of lifeline that is both literal and metaphorical. It can be hard to make visual art when the whole world is burning. But in fleeting moments of clarity, I think, well, if there’s no more art, I won’t survive. Yet it’s the daily justifications for it that can feel inconsequential.

SV: To be honest, I haven’t yet found a super convincing moral or ethical argument, not that there isn’t one, but I haven’t been able to attach myself to one. I try not to make things unless I really want to make them. I don't make a lot of stuff, you know, and I feel there is an economy to what I make. I have to have a pretty strong desire to try something, and then I just try to rely on that feeling.

JP: You wrestle with it. Well, yeah, that makes you human. When you have that desire to finally make something that you’ve been working through, does it emerge from a desire to see the thing you’re imagining? Is it a desire to touch it, to look at it?

SV: Yes. I think, well, no one’s going to make that if I don’t make it.

![]()

Stefanie Victor, Untitled (eyes for Geta I), 2016, white bronze, nickel, paint, brass and copper tubing, 3 1/2 x 4 1/2 x 2 inches.

JP: And what is the form, the physical presence, of the Geta works?

SV: I made four pieces in metal and one in clay. Three are “Geta eyes” and two are “Geta hands.” The eyes are two conjoined circles with a tube in the center of each roughly the size of a finger. The hole is like a pupil but also a hole for a finger. To be honest, I had thought about the form before I knew what it was, or that it would be named for her.

JP: The interlocking circles?

SV: Yes, just as a kind of shape idea, basically, and then when I saw Brătescu’s film and it’s subtitle, I started thinking about them in relation to the way she uses her eyes, her hands. You wrote about this in your book [Dance with Camera, 2010]: that the camera orchestrates the relationship between the eye and the dancing body. In Brătescu’s film, the eye is the camera eye but its job is to foreground touch. The idea was that those pieces would deliberately link the eye and hand. The “Geta hands” have articulated “joints.” They’re not kinetic pieces but they have joints that could move. I was thinking about the way that she mapped the bones of her hands, how she moves her hands.

Stefanie Victor: I’m working on whatever I can for the upcoming exhibition, but much of the production is paused. But what I’m making now is a body of work I’ve had in mind for about two years, which essentially extends my work from individual objects to groups of objects that repeat or vary, and create spatial rhythms around the room. There will be four components and they’re currently in various stages of completion. So, I started working on another little project that is not close to being ready for the world and feels like something that probably wouldn’t have happened if we weren’t sheltered in our home the way we are. I’m looking at the soap dish in my bathroom, which has these indentations that grip the soap but are also ornamental.

JP: Is it the kind of ceramic soap dish that’s tiled onto the wall?

SV: Exactly. It’s embedded in the infrastructure, if I can call it that. I’m thinking about them like a series of horizontal paintings or little horizontal friezes.

JP: So you’re looking at the objects around you, in your home. This isn’t such a departure from the way you work, right?

SV: That’s true, but it feels somehow both especially apt and especially absurd now. I’m spending so much time in my apartment, looking even more at my interior space, while there’s so much happening outside that’s vastly more important, and bigger, and heavier than I can really comprehend.

JP: We’re all hand washing and handwringing.

SV: The soap dish is really mundane, just a little part of my home, but it’s led to some new ideas.

JP: Is your studio in your home?

SV: Yes. I’ve always worked at home, except for when I was in grad school. I’ve taught high school for the past ten years, and so just on a very basic, day-to-day life habit, having the ability to get out of bed on Saturday, work on something for forty-five minutes, run an errand and then do some more work, has always felt right for me. I’m not the kind of artist that goes at a painting for eight hours at a stretch. And I have a son, so, you know, I can make him a sandwich and then he gets absorbed in his Legos and I can go in and work.

JP: I’ve been thinking about artists working at home, for so many pandemic-related reasons, but also because I’m writing about Ruth Asawa, an artist whose art and life were so consciously intertwined. She made her art at home, alongside her roles as a mother, wife, friend, activist, and teacher. I think many of us have bought into a fantasy of what a so-called working artist looks like, that there’s one “right” way to fulfill that role, yet we recognize that fantasy is based on a white, hetero, male, Western canon. But this idea of domestic space in your work, this idea of working as one can, when one can, is typically gendered female. You’ve made several bodies of work named for women artists. Would you talk through some of those? Perhaps begin with the Geta series?

SV: I came across Geta Brătescu’s work in a collection show at MoMA [Transmissions: Art in Eastern Europe and Latin America, 1960–1980, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, 2016], these smallish textile works that were really striking and beautiful [Medea’s Hypostases series, 1980, drawing with sewing machine on textile]. I’ve always been interested in fabric and textile art, which is probably why I looked her up later. I discovered this quite wide-ranging body of work that, to be honest, I just connected with on a visual level. I got books on her work, and I looked at the pictures before I read anything. I came across this film called Hands (For the Eye, the Hand of My Body Draws My Portrait) [1977, black-and-white silent film, 7:30 minutes]. It’s an overhead shot of her hands at her desk in her studio. And one of the first things that crossed my mind was how similar it was to some videos that I’d tried to make a couple of years earlier. My work is small and I’m working with my hands, and working with everyday objects at least to make forms and shapes and models. This isn’t to say that I think her work, which is coming from a particular place and time, is coming from the same place I am. But I’m looking at it, and thinking, this is me. Or, this feels like the under layer of my process, the circling of the hands, the mapping of her bones with a marker, the twisting of things and throwing things out. Her film is a bit more theatrical, but it felt like this kind of connection through process. My work doesn’t scream process; it’s quiet and finished in ways that you don’t really see my hand. So in a sense naming my work “for Geta” felt like a way to connect through the work behind the work. It also felt like license to pursue forms that directly come from the body, and the hand and eye in particular.

JP: And in any sense did her way of working give you a feeling of confirmation?

SV: Yes, totally. It’s like when you’re reading a book and the author has an insight into a thought process that you didn’t even know you were having.

Stefanie Victor with Geta Brătescu, installation view, Adams and Ollman, 2018.

JP: I know exactly what you mean. I have that feeling all the time when I read fiction. It’s like a transmission through time and space, a confirmation that there is a kind of timelessness or an energy that threads through our bodies. I think it can be incredibly moving to linger in that sensation of universality.

I try not to make things unless I really want to make them. I don't make a lot of stuff, you know, and I feel there is an economy to what I make. I have to have a pretty strong desire to try something, and then I just try to rely on that feeling.

SV: Especially right now as we’re all experiencing some kind of loss of connection. The artists that I’ve responded to the most don’t know me, but I think this kind of connection gives me a stronger ground on which to stand. I think that there’s something that can be isolating about making art. I think it’s hard to justify making visual art. You know, when there’s so many other ways you can use your time, but if I didn’t feel those relationships to other artists, I would feel lost.

JP: Those connections are a kind of lifeline that is both literal and metaphorical. It can be hard to make visual art when the whole world is burning. But in fleeting moments of clarity, I think, well, if there’s no more art, I won’t survive. Yet it’s the daily justifications for it that can feel inconsequential.

SV: To be honest, I haven’t yet found a super convincing moral or ethical argument, not that there isn’t one, but I haven’t been able to attach myself to one. I try not to make things unless I really want to make them. I don't make a lot of stuff, you know, and I feel there is an economy to what I make. I have to have a pretty strong desire to try something, and then I just try to rely on that feeling.

JP: You wrestle with it. Well, yeah, that makes you human. When you have that desire to finally make something that you’ve been working through, does it emerge from a desire to see the thing you’re imagining? Is it a desire to touch it, to look at it?

SV: Yes. I think, well, no one’s going to make that if I don’t make it.

Stefanie Victor, Untitled (eyes for Geta I), 2016, white bronze, nickel, paint, brass and copper tubing, 3 1/2 x 4 1/2 x 2 inches.

JP: And what is the form, the physical presence, of the Geta works?

I try to think about that slippage between knowing what something is, or feeling like you do, and its operation as something else, something other.

SV: I made four pieces in metal and one in clay. Three are “Geta eyes” and two are “Geta hands.” The eyes are two conjoined circles with a tube in the center of each roughly the size of a finger. The hole is like a pupil but also a hole for a finger. To be honest, I had thought about the form before I knew what it was, or that it would be named for her.

JP: The interlocking circles?

SV: Yes, just as a kind of shape idea, basically, and then when I saw Brătescu’s film and it’s subtitle, I started thinking about them in relation to the way she uses her eyes, her hands. You wrote about this in your book [Dance with Camera, 2010]: that the camera orchestrates the relationship between the eye and the dancing body. In Brătescu’s film, the eye is the camera eye but its job is to foreground touch. The idea was that those pieces would deliberately link the eye and hand. The “Geta hands” have articulated “joints.” They’re not kinetic pieces but they have joints that could move. I was thinking about the way that she mapped the bones of her hands, how she moves her hands.

JP: You mentioned you build models.

SV: Yes, tons of them, in paper and clay and pipe cleaners, to figure things out. I have to have a starting point, but I don’t know where I’m going to end up. The ideas come through making something, then making iterations, thinking about what material it should be. And then, should it be installed like this? Or should it be on the table? I could never conceptualize it without making and trying things.

JP: Your finished work is often highly crafted. Do you suspect that you might be getting better at making? Do you find yourself becoming more skilled? Or do you find yourself resisting expertise, or seeking new formal and material investigations each time so as to set new challenges for yourself?

SV: I think there are so many sides to those questions. Okay, first of all, everything always feels really hard. I don’t feel that anything I do as an artist has become easier. Whether or not I’m working with a material that I have more mastery over, there’s always something else that’s a problem, or a goal that’s not met. It always feels excruciating, for sure. I return to strategies or materials that feel like they hold more possibilities than could be contained in a single piece and that I feel compelled to keep looking into. I’ve considered a few times the way things move into the wall, and the relationship between something embedded and something protruding.

JP: So at this point in your practice you’re trying out different materials and techniques?

SV: I love working with my hands. I love learning new material processes. But I try to make sure that I’m working with a material because it’s the right material for the idea.

JP: The material investigation has to match the idea, the material form the intended installation?

SV: Exactly. Every new form presents its own needs, and difficulties. But I really don’t want the effort or the labor to be perceived primarily or even secondarily. The point of my labor is to make this thing that at first looks fabricated and of the ‘real’ world but which has a quality of strangeness that I think comes in part from it being made by hand. The process feels to me less about skill or craft and more about patience and attention, like making an observational drawing but of something that doesn’t quite exist.

JP: Take me through the works you’re making for your February exhibition [later resecheduled to September] at the gallery, the metal pieces, the ceramic pieces, the glass, and how they’re going to be installed.

SV: The way I’m thinking about the show is that, as opposed to a room of discrete objects, there will be a series of objects that are installed in patterns or rhythms around the gallery. I’m thinking about repeating motifs in a domestic space, like moldings, drawer pulls, cords, and the repetition of my own movements at home and in my studio.

JP: Is there a specific reference for the shapes of the glass sculptures?

SV: I was thinking about the shape of a brow, the bone structure of the top of your face. I was looking at the shape of mine, my son’s, my husband’s, mapping that out. I made a lot of different versions of that kind of form. I thought at first it might exist in different versions. The shape is also like an anvil, or a tool. They’re going to be hung on L-hooks, the way you’d hang, say, a hammer, so it feels like something you use for something. Once I began working on this piece, I started to see this arc shape everywhere. It’s a shape that’s like, open source—everywhere, available. It has an ornamental quality and a feminine quality and a sharp quality and a human quality and a tool-like quality.

JP: At what height will they be installed?

SV: Molding height, and that will depend on the overall height of the room I’m installing. I decided to cast them in glass because I wanted them to be sort of invisible. There’s a slight haze or ghostliness to the glass, so that when they’re lit you see the articulation of the form.

The process feels to me less about skill or craft and more about patience and attention, like making an observational drawing but of something that doesn’t quite exist.

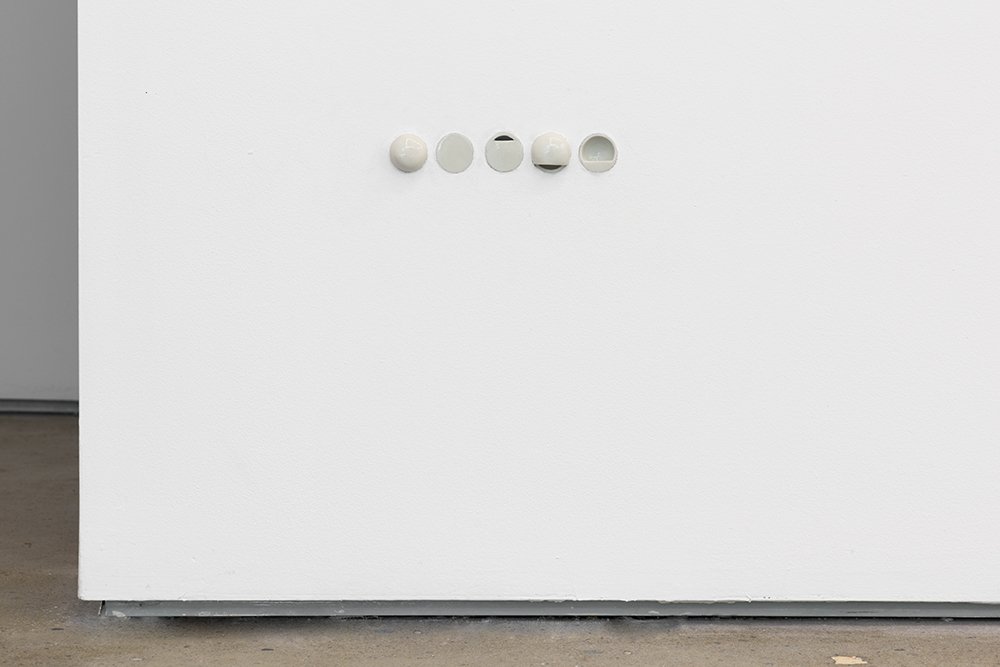

Another body of work is composed of sets of porcelain half-moon shapes, like a drawer pull. As I started thinking about these, like the brow shape, I started seeing these little vents with half coverings everywhere. These will be embedded in the wall, in sets of five, in relation to digits, low to the ground, maybe baseboard height, at varying intervals. The third aspect of the show are these rope forms made from twisting thin wire in the same way that one would twist thread to make a rope. I’m thinking of them as operating almost like drawings, where they really just become these blackened lines against the wall. They’ll be installed among the gallery’s three walls in irregular ways, with various tensions.

JP: So the two ends of a rope piece will be in the same wall? And do they have different lengths?

SV: Yes. And then they’re also set at different angles. So the glass and ceramic works are horizontal, quiet lines that will be countered by these diagonals that stretch and pull in different ways.

JP: Finally, you’ve mentioned the work of Scott Burton, and specifically a little-known performance work. I’m a diehard Burton fan, so I’m delighted to see his work picked up by young artists. How does his work play through your work for this show?

![]()

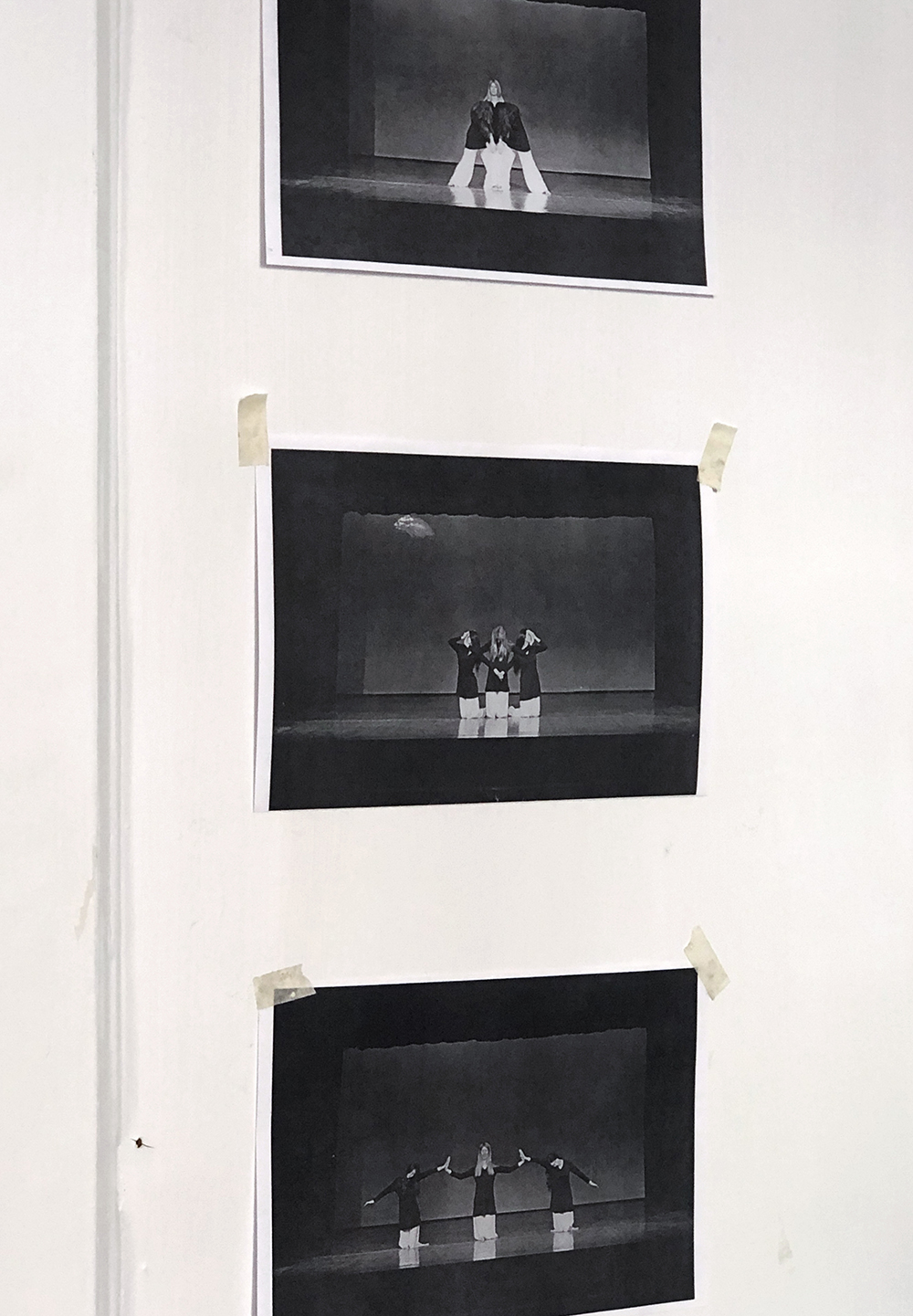

Artist’s photo of the studio showing documentation of Scott Burton’s 30 Compositions, 1970.

SV: I think the most obvious way that I’m indebted to Burton, perhaps more generally, is the way his most well-known works are both furniture and sculpture, and their significance resides in that deliberate tension. And that resonates with me as I navigate how to make art that gestures out of itself, that gestures back into life.

Another quality of his work I appreciate is what Lynne Cooke described [in Scott Burton Sculptures 1980-89] as “very low profile”; it sort of slips into public spaces, not as a capital “A” art monument, but as a seat—albeit a perhaps uncomfortable one. [Laughs] That subtlety, that non-announcement is what is interesting to me. I think my work tries to do this in different ways. I try to think about that slippage between knowing what something is, or feeling like you do, and its operation as something else, something other. As with Geta Brătescu, I got really interested in the performative qualities of his work. But, I’m very much not a performance artist. I’m like an enclosed artist. [Laughs]

JP: Good one. So again, these kinds of transmissions among artists…

SV: Yes. So in a recently published book of Burton’s writings [David J. Gesty, Scott Burton: Collected Writings on Art & Performance 1965–1975] there’s a text which is a performance Burton gave about his early performances, and he mentioned many pieces I had never heard of. I learned that MoMA holds his archives so I went to take a look. I came across a file of black-and-white photographs that document a performance with three women on a stage [30 Compositions, 1970]. First, I was struck by the female form in this work. Burton’s sculptures are objects that we can sit or lie on, or we imagine ourselves sitting or lying on, and when we do so, our bodies take on particular shapes. But, in the case of this performance, he’s just using bodies on their own. The performance is visually striking. The women make these unusual, beautiful, abstract shapes. Burton is exploring posture itself through a kind of systematic formalism, which interests me because he later disavows that kind of concern. He talked about the idea of art outside the realm of the individual studio artist, that art should face out not in, operate alongside politics and culture, that it should be actually functional not just as furniture but for society. But there is also this really beautiful and powerful aesthetic dialogue in some of the pieces themselves as forms, as objects.

JP: I’m so struck by these images, which I’ve never seen until you introduced them to me. This piece, while performed live, seems made for the camera. In fact, it’s like the photographs transform the work into dance. But it wasn’t a dance, per se. It was thirty poses punctuated by blackout. The “movement” is all between the images, imagined now, but at the moment of its performance, merely the movement required to assume the next pose.

SV: I love that idea of imagined movement, because I also see them as this stillness that implies gesture. I’m thinking about showing documentation of 30 Compositions in the context of this next project because I want to draw a connection between that latent motion in his work, and the kind of smaller bodily gestures that are informing my sculptures, albeit for me, in the context of privacy, of domestic space. Usually, art that uses bodies is not still. But this work diminishes the overt expressiveness that is traditionally associated with gesture. It’s a quietness I relate to.

Jenelle Porter is a curator and writer. She has organized a range of exhibitions, including Less Is a Bore: Maximalist Art & Design (2019) and Fiber: Sculpture 1960–present (2014), Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston; Mike Kelley: Timeless Painting, Hauser and Wirth, New York (2019); and Dance with Camera (2009) and Dirt on Delight: Impulses That Form Clay (2009), Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia; as well as monographic exhibitions on artists such as Nick Cave, Trisha Donnelly, Jeffrey Gibson, Charline von Heyl, Christina Ramberg, Matthew Ritchie, Kay Sekimachi, and Arlene Shechet, among many others. She has held curatorial positions at ICA/Boston, ICA Philadelphia, Artists Space, Walker Art Center, and Whitney Museum of American Art. She lives in Los Angeles.

SV: Yes, tons of them, in paper and clay and pipe cleaners, to figure things out. I have to have a starting point, but I don’t know where I’m going to end up. The ideas come through making something, then making iterations, thinking about what material it should be. And then, should it be installed like this? Or should it be on the table? I could never conceptualize it without making and trying things.

JP: Your finished work is often highly crafted. Do you suspect that you might be getting better at making? Do you find yourself becoming more skilled? Or do you find yourself resisting expertise, or seeking new formal and material investigations each time so as to set new challenges for yourself?

SV: I think there are so many sides to those questions. Okay, first of all, everything always feels really hard. I don’t feel that anything I do as an artist has become easier. Whether or not I’m working with a material that I have more mastery over, there’s always something else that’s a problem, or a goal that’s not met. It always feels excruciating, for sure. I return to strategies or materials that feel like they hold more possibilities than could be contained in a single piece and that I feel compelled to keep looking into. I’ve considered a few times the way things move into the wall, and the relationship between something embedded and something protruding.

JP: So at this point in your practice you’re trying out different materials and techniques?

SV: I love working with my hands. I love learning new material processes. But I try to make sure that I’m working with a material because it’s the right material for the idea.

JP: The material investigation has to match the idea, the material form the intended installation?

SV: Exactly. Every new form presents its own needs, and difficulties. But I really don’t want the effort or the labor to be perceived primarily or even secondarily. The point of my labor is to make this thing that at first looks fabricated and of the ‘real’ world but which has a quality of strangeness that I think comes in part from it being made by hand. The process feels to me less about skill or craft and more about patience and attention, like making an observational drawing but of something that doesn’t quite exist.

JP: Take me through the works you’re making for your February exhibition [later resecheduled to September] at the gallery, the metal pieces, the ceramic pieces, the glass, and how they’re going to be installed.

SV: The way I’m thinking about the show is that, as opposed to a room of discrete objects, there will be a series of objects that are installed in patterns or rhythms around the gallery. I’m thinking about repeating motifs in a domestic space, like moldings, drawer pulls, cords, and the repetition of my own movements at home and in my studio.

JP: Is there a specific reference for the shapes of the glass sculptures?

SV: I was thinking about the shape of a brow, the bone structure of the top of your face. I was looking at the shape of mine, my son’s, my husband’s, mapping that out. I made a lot of different versions of that kind of form. I thought at first it might exist in different versions. The shape is also like an anvil, or a tool. They’re going to be hung on L-hooks, the way you’d hang, say, a hammer, so it feels like something you use for something. Once I began working on this piece, I started to see this arc shape everywhere. It’s a shape that’s like, open source—everywhere, available. It has an ornamental quality and a feminine quality and a sharp quality and a human quality and a tool-like quality.

JP: At what height will they be installed?

SV: Molding height, and that will depend on the overall height of the room I’m installing. I decided to cast them in glass because I wanted them to be sort of invisible. There’s a slight haze or ghostliness to the glass, so that when they’re lit you see the articulation of the form.

The process feels to me less about skill or craft and more about patience and attention, like making an observational drawing but of something that doesn’t quite exist.

Another body of work is composed of sets of porcelain half-moon shapes, like a drawer pull. As I started thinking about these, like the brow shape, I started seeing these little vents with half coverings everywhere. These will be embedded in the wall, in sets of five, in relation to digits, low to the ground, maybe baseboard height, at varying intervals. The third aspect of the show are these rope forms made from twisting thin wire in the same way that one would twist thread to make a rope. I’m thinking of them as operating almost like drawings, where they really just become these blackened lines against the wall. They’ll be installed among the gallery’s three walls in irregular ways, with various tensions.

JP: So the two ends of a rope piece will be in the same wall? And do they have different lengths?

SV: Yes. And then they’re also set at different angles. So the glass and ceramic works are horizontal, quiet lines that will be countered by these diagonals that stretch and pull in different ways.

JP: Finally, you’ve mentioned the work of Scott Burton, and specifically a little-known performance work. I’m a diehard Burton fan, so I’m delighted to see his work picked up by young artists. How does his work play through your work for this show?

Artist’s photo of the studio showing documentation of Scott Burton’s 30 Compositions, 1970.

SV: I think the most obvious way that I’m indebted to Burton, perhaps more generally, is the way his most well-known works are both furniture and sculpture, and their significance resides in that deliberate tension. And that resonates with me as I navigate how to make art that gestures out of itself, that gestures back into life.

Another quality of his work I appreciate is what Lynne Cooke described [in Scott Burton Sculptures 1980-89] as “very low profile”; it sort of slips into public spaces, not as a capital “A” art monument, but as a seat—albeit a perhaps uncomfortable one. [Laughs] That subtlety, that non-announcement is what is interesting to me. I think my work tries to do this in different ways. I try to think about that slippage between knowing what something is, or feeling like you do, and its operation as something else, something other. As with Geta Brătescu, I got really interested in the performative qualities of his work. But, I’m very much not a performance artist. I’m like an enclosed artist. [Laughs]

JP: Good one. So again, these kinds of transmissions among artists…

SV: Yes. So in a recently published book of Burton’s writings [David J. Gesty, Scott Burton: Collected Writings on Art & Performance 1965–1975] there’s a text which is a performance Burton gave about his early performances, and he mentioned many pieces I had never heard of. I learned that MoMA holds his archives so I went to take a look. I came across a file of black-and-white photographs that document a performance with three women on a stage [30 Compositions, 1970]. First, I was struck by the female form in this work. Burton’s sculptures are objects that we can sit or lie on, or we imagine ourselves sitting or lying on, and when we do so, our bodies take on particular shapes. But, in the case of this performance, he’s just using bodies on their own. The performance is visually striking. The women make these unusual, beautiful, abstract shapes. Burton is exploring posture itself through a kind of systematic formalism, which interests me because he later disavows that kind of concern. He talked about the idea of art outside the realm of the individual studio artist, that art should face out not in, operate alongside politics and culture, that it should be actually functional not just as furniture but for society. But there is also this really beautiful and powerful aesthetic dialogue in some of the pieces themselves as forms, as objects.

JP: I’m so struck by these images, which I’ve never seen until you introduced them to me. This piece, while performed live, seems made for the camera. In fact, it’s like the photographs transform the work into dance. But it wasn’t a dance, per se. It was thirty poses punctuated by blackout. The “movement” is all between the images, imagined now, but at the moment of its performance, merely the movement required to assume the next pose.

SV: I love that idea of imagined movement, because I also see them as this stillness that implies gesture. I’m thinking about showing documentation of 30 Compositions in the context of this next project because I want to draw a connection between that latent motion in his work, and the kind of smaller bodily gestures that are informing my sculptures, albeit for me, in the context of privacy, of domestic space. Usually, art that uses bodies is not still. But this work diminishes the overt expressiveness that is traditionally associated with gesture. It’s a quietness I relate to.

Jenelle Porter is a curator and writer. She has organized a range of exhibitions, including Less Is a Bore: Maximalist Art & Design (2019) and Fiber: Sculpture 1960–present (2014), Institute of Contemporary Art/Boston; Mike Kelley: Timeless Painting, Hauser and Wirth, New York (2019); and Dance with Camera (2009) and Dirt on Delight: Impulses That Form Clay (2009), Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia; as well as monographic exhibitions on artists such as Nick Cave, Trisha Donnelly, Jeffrey Gibson, Charline von Heyl, Christina Ramberg, Matthew Ritchie, Kay Sekimachi, and Arlene Shechet, among many others. She has held curatorial positions at ICA/Boston, ICA Philadelphia, Artists Space, Walker Art Center, and Whitney Museum of American Art. She lives in Los Angeles.