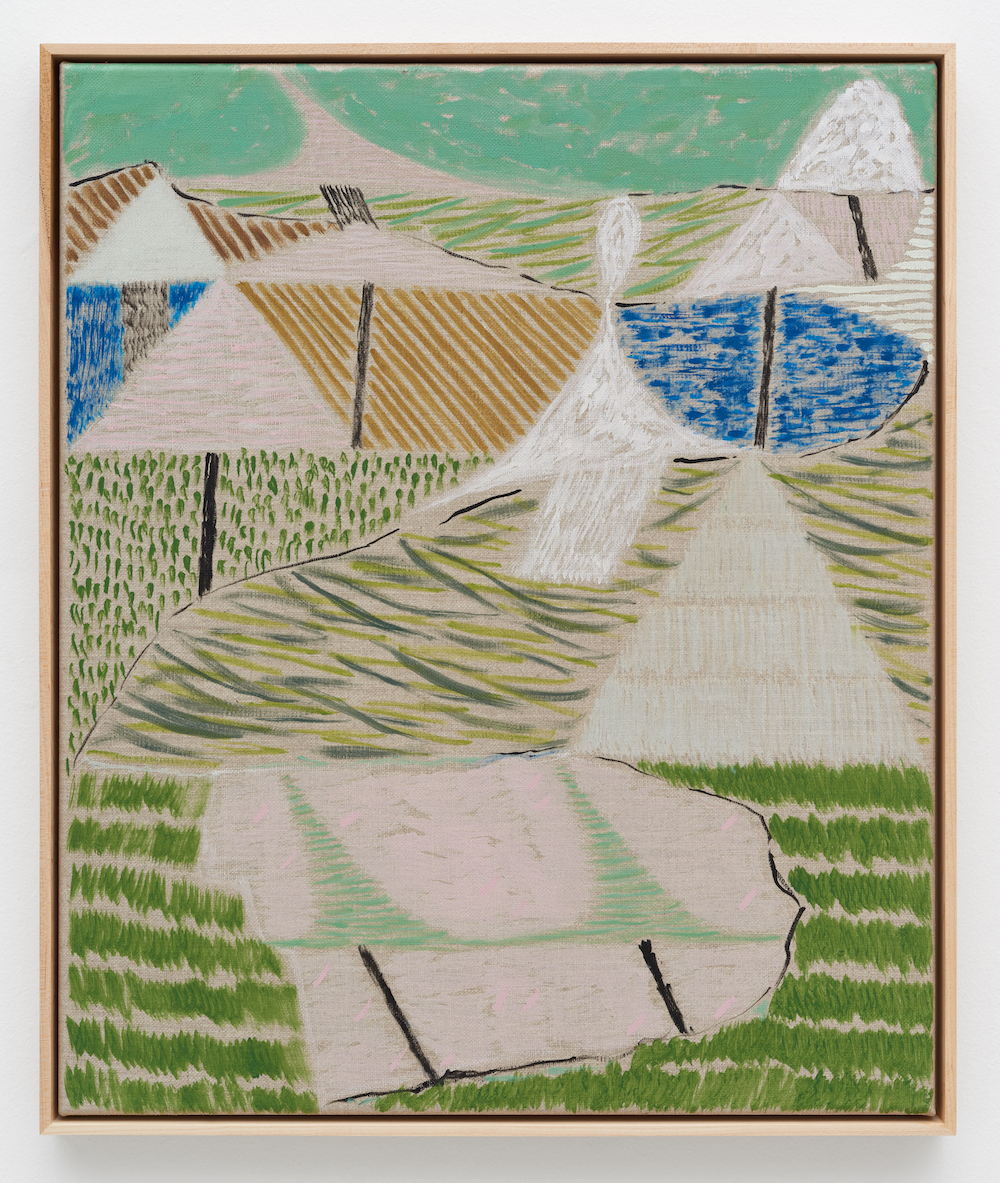

Rob Lyon, Sweet undulatons/ascension, 2022. Photo: Theo Cristelis.

William Pym on Rob Lyon, September 2022.

Rob Lyon is a landscape painter from a rural parcel of Southern England. He paints the landscape around where he lives, which is where he grew up and where he returned as an adult. That’s how it goes sometimes. Lyon is self-taught, in that he wasn’t reared on art history and he didn’t go to art school. Lyon is learning what he’s doing as he does it, sometimes for the first time, sometimes by building on something that worked before.

He is buoyed by a belief in primal and nature-based knowledge, which we call intuition, rather than a Vitruvian approach, where beauty is quantified relative to the human body. He finds his way by feel, rather than measurement or definition. “You can’t anthropomorphize the planet,” he tells us. And since Lyon does not have the art-school grad’s beefy strength of purpose, that faith you pay for via apprenticeship to elders and a tribal alignment to peers, he is strengthened by the inherent value of production and the solidarity that every painting offers him. Make the object your comrade, per the Soviet art critic Boris Arvatov. The paintings reassure him he is on the right track. Each one is a marker.

From canvas to canvas and within each composition, Rob Lyon’s paintings are a navigation through nature. There is repetition, a pattern or a tree that you may have seen before, or one just like it. There are pathways and dead ends. There are holes and organic framing devices. Most importantly there are abrupt shifts in scale and a non-stop interplay between positive and negative space. These are the great hallmarks of the natural world, where there is no hierarchy of value and no arbiter of what’s big and what’s small. Within this space, revelations come where they come, which is everywhere.

“If we join Lyon and reject linear thinking in the name of redefining progress, we may resist the inevitability of man’s progress leading the way.”

Between 1968 and 1970, the British government undertook the largest and most costly planning commission in the nation’s history to figure out where a third London airport could be sited. The investigation settled upon a spot northwest of the city full of old-growth forests, farmland, a Medieval church, a Norman mound, and a village where people had lived for at least a thousand years. All of it was to be scythed by the blade of capital, then coated in carbon. Two farmers began a protest and made enough noise that the project was formally abandoned in 1971. There is a plaque quoting Henry James where the center of the airport would have been, declaring it ‘midmost unmitigated England’. The resistance of the people of Cublington and their supporters represents the last stand of the last environmental movement that had traction—a movement that won. In the years since the rejection of that absurd third airport, nature has lost its dignity in the war with capital.

“From canvas to canvas and within each composition, Rob Lyon’s paintings are a navigation through nature... there is no hierarchy of value and no arbiter of what’s big and what’s small. Within this space, revelations come where they come, which is everywhere.”

Cublington Spinney memorial. Photo: Philip Jeffrey

“Art history loses authority in a moment when the meaning of progress is up for grabs,” Lyon tells us, stating the quiet urgency of his enterprise and explaining what a gift it is to be self-taught, operating without a map, drawing the map yourself by entering the landscape and accepting it as the teacher. “Nature revolves, but man advances” wrote Edward Young in his legendarily gloomy Night-Thoughts of 1742. If we join Lyon and reject linear thinking in the name of redefining progress, we may resist the inevitability of man’s progress leading the way. We can invert it. Man advances, but nature revolves. How about that? The pattern and the shape of Rob Lyon’s work, the answers in the form of inquiry and their quiet resistance born of true faith, speak of an approach for today.

William Pym is a writer based in Kent, England. His most recent essay, a tract on the history of industrial processes, their depiction in art, and the work of Mika Rottenberg, appeared in the artist’s monograph published by the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk. He is currently writing a treatise about love, sex, David Ruffin and masculinity entitled I Feel it Coming.