Indie Folk: A Conversation with Melissa Feldman and Grace Kook-Anderson

Grace Kook-Anderson, Arlene & Harold Schnitzer Curator of Northwest Art at the Portland Art Museum, speaks with independent curator and writer Melissa Feldman on the occasion of Indie Folk: New Art from the Pacific Northwest, organized by Feldman.

Grace Kook-Anderson: I’m pleased to be in conversation with you here today, Melissa -- thank you so much. Given my field of focus, it’s great to see this exhibition and your thinking around some of the characteristics of our region.

Melissa Feldman: Thank you Grace, great to be here. Indie Folk, which is viewable at adamsandollman.com, includes works by seventeen artists, as well as a 25-minute playlist of indie folk music—which obviously inspired the show—put together by Eric Isaacson of Mississippi Records, a Portland-based label and record store. It really sets the mood!

You’ll also see installation views—none of this work actually crossed the threshold of the gallery, they are all virtual installation views. There are short texts written by myself and others that are comprised of email conversations I had with the artists -- so there is a variety of different texts presented as part of the exhibition.

GKA: Can you talk about how you came about this exhibition and its title came about? It’s a great group of seventeen artists, and they’re each represented by one or two pieces in the exhibition that create a really nice conversation together.

MF: The title came about when I discovered Indie Folk, the music genre. I wanted a soundtrack to accompany the show, and I initially thought it would be folk music, because I noticed that there are a lot of bands, even from my 22-year old son’s generation, who are dedicated to the folk genre. Then I discovered that there is actually a genre called indie folk—which I know I probably shouldn’t admit to not knowing about—but it is a genre that originated in the Pacific Northwest. So, there was my soundtrack and there was my title.

GKA: And then how does that translate into the visual arts specific to the exhibition?

MF: Well, indie folk is “updated” folk music—folk combined with other genres. You’ll see in the soundtrack that there is quite a lot of variety, just like there is quite a variety of work in the show. These artists take traditional techniques from enamel painted glass and hand-tooled wood, to quilt-making and indigenous basket weaving, and updating them so that they speak to our contemporary situation.

Joe Feddersen

High-Voltage Tower, 2015

waxed linen basket

9 x 6 x 6 inches

For example, on Indigenous artist Joe Fedderson’s woven baskets, you have his geometric designs which are traditional to that form. In Joe’s work, however, it takes the form of electrical pylons—referring to systems of our contemporary civilization in a very pointed way.

GKA: In putting together this exhibition, how did you think about the Northwest region? What does the Northwest mean to you specifically in the context of this exhibition?

MF: I’m originally from New York City, but I was based on the west coast for almost twenty years -- seven of those years in Seattle. The exhibition came from work I was seeing around me in the Pacific Northwest, and noticing that it had this particular folk or vintage quality. There was a real interest in the handmade, and work that could be understood as both art and a utilitarian object. I’m still figuring out how this reflects a Northwest identity.

Another aspect of the Pacific Northwest that is a real inspiration for the show is the great regard and presence of Indigenous culture in this part of the world. I’ve never experienced anything like it. Artists over the years have been inspired by the work by Indigenous artists from this region. For example, the Northwest Mystics were looking at Coast Salish—the kind of imagery and style of figuration and patterning from that culture.

I think another aspect of the Northwest that overlaps with Indigenous culture is a great respect for nature. And I think there’s something about the old world to that—the way things used to be when we were more connected to the natural world, and working in concert with it.

I noticed this was a common thread between artists of this region. As curators it’s our job to be observant and to be knowledgeable about what’s going on elsewhere. So for example, in a lot of scenes elsewhere around the world you see a really strong influence of minimalist and conceptual art—you don’t see that very much in the Pacific Northwest.

Another thing that I was excited about was the opportunity to bring some critical focus onto the scene there, which hasn’t really had a movement for seventy years, I’d say. I think the last group of artists who spoke to a moment and had related styles was the Northwest Mystics. I think what’s going on in the Northwest right now is very exciting.

GKA: I think that’s really interesting—that idea that movements and collectivity as sort of a shared sensibility is not as prominent in contemporary art in the way that it maybe used to be, even through Modernism in a lot of ways. As you point out, this is the first time they’re shown together in this context. Even though there’s a common characteristic that you’ve identified, these are artists that haven't necessarily written a manifesto or made a concerted effort to move together in this kind of cohesive way. I think that, too, defines our current moment in contemporary art, where it’s so much of everything. Artists are not committed to a medium—it’s more about what needs to be said and the materials don’t dictate what that is necessarily.

D.E. May

Untitled #273, 2019

ink, gouache, found papers, tape and graphite on cardboard

7 1/4 x 5 x 1 3/4 inches

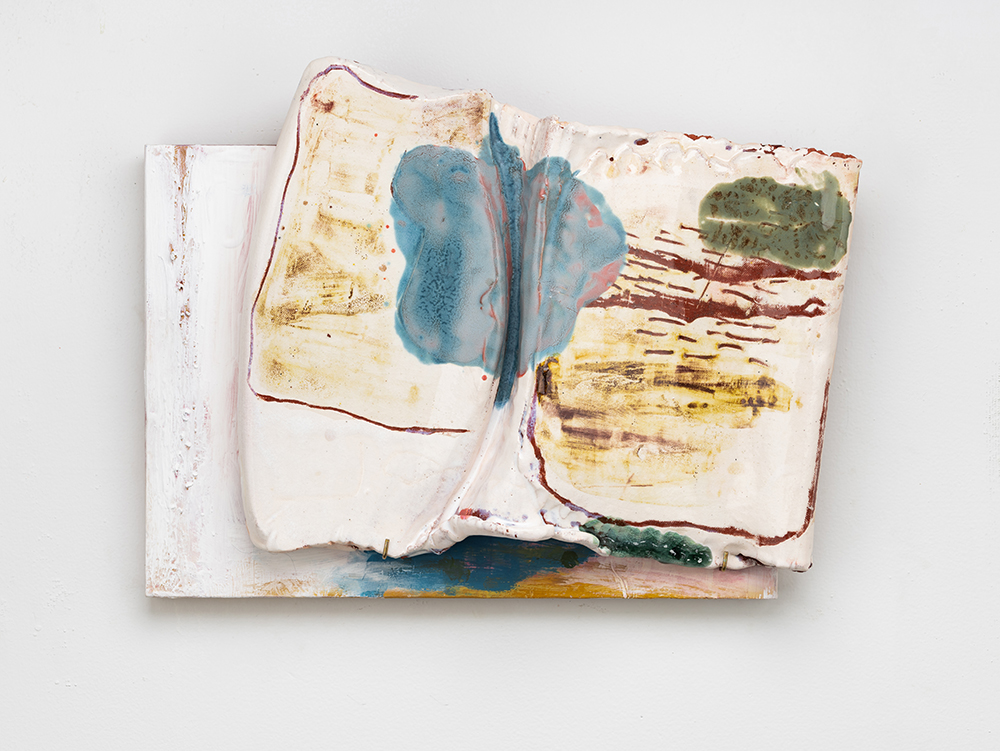

Jessica Jackson Hutchins

Butterfly Kiss, 2019

flashe and acrylic and wood stain on board with glazed ceramic

11 3/4 x 15 1/2 x 2 3/4 inches

Blair Saxon-Hill

On Deck, 2018

LA metal, wash cloth, tin can, railing element, wood, rain jacket, fiber reinforced plaster, gouache, foam

84 x 48 x 8 inches

MF: I think that for these artists though, the materials are speaking to them. Blair Saxon-Hill, for example, scavenges materials for her works, as do Jessica Jackson Hutchins and D.E. May. Both of their work has a sort of patina of age. There’s a history to the materials—whether it be a dress or a piece of styrofoam—being scavenged for the works.

Sky Hopinka

Lore, 2019

Total run time: 10:16

16mm to HD video, stereo, color

POR

Joe Feddersen

Floating By, 2016

monoprint with spray paint, relief, collage

30 x 22 inches

GKA: Yes, the artists in Indie Folk are not monogamous to the sanctity of painting or clay—they use a lot of different materials. I appreciate that you’ve also included Native American artists like Joe Fedderson and Sky Hopinka. I like the inclusion of Marita Dingus, too. Can you talk about the inclusion of her work in this exhibition? I think there are some great connections with Blair Saxon-Hill as well Jessica Jackson Hutchins.

Marita Dingus

Silver Fence, 2003

pull tabs, wire

48 x 48 x 2 inches

MF: I would say that the three artists you mentioned—all of their work comes out of domestic space. Marita Dingus’s work draws from traditional African art and spiritual practices for her in-situ outdoor sculptures. She lives in the woods outside of Seattle in the house she grew up in, and she has basically created a sculpture garden around her house.

GKA: We’ve previously talked about your interest in intergenerational artists being shown together. Can you talk about this in terms of your own curatorial work but specifically in this exhibition?

Denzil Hurley

Strip Glyph #1, 2019

oil on linen

28 1/2 x 19 1/2 x 1 1/2 inches

Gaylen Hansen

White Fish and Blue Glove, 2019

acrylic on canvas

48 x 60 inches

MF: If I can break down boundaries in my shows, I do. So if work can be intergenerational—great. If it makes sense to have a lot of different mediums, I’m happy. Here, the more senior artists, which would include Marita Dingus, Joe Fedderson, Denzil Hurley, Gaylen Hansen—they establish a bit of a lineage for this kind of work. I think that’s an important role of the curator—to help understand what’s going on now, and how it might relate to what’s happened before.

GKA: I want to wrap it up by thinking about creating an exhibition that lives online. I really enjoyed browsing through Indie Folk, not only with the installation images but looking at the checklist of all the works, as well as texts by the artists and yourself. I also loved the notes section—which I encourage everyone to browse through—because it acts as an index in a way. I was particularly taken with Jeffry Mitchell’s image that inspires the idea of lacing or a canopy in his work. And then additionally, to listen to the playlist. To have a multisensory experience is really great, especially at a time when many of us are stuck in our houses right now. The playlist really plays into the whole experience quite nicely. Can you talk about all of this as a way to put together an exhibition? Were you thinking about the show three-dimensionally as well?

MF: No, I wasn’t thinking three-dimensionally—I was only thinking two-dimensionally. It wasn’t really until we started playing around with the installation views that I started thinking about conversations between individual works. I’ve always wanted to have a show with music, so it was great to take advantage of the multimedia that an online show offers. I did miss doing studio visits and installing a show—two of my favorite parts of our work. At the same time, it felt good to be able to put something out there especially under the circumstances.

GKA: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Cappy Thompson

Blue Tree Keeper, 2015

vitreous enamel reverse-painted on blown glass

11 x 10 x 6 inches

Warren Dykeman

16 KON, 2019

acrylic and graphite on muslin

43 x 70 inches

MF: These artists have never been shown together this way, with a thematic connection. For example, an artist like Cappy Thompson who paints with enamel on glass as well as other techniques involving glass— her work is treated as a craft. I don’t see her work that way, and I think that there are a lot of connections between how she is treating figuration in her work—looking at ancient Indian art, Pennsylvania Dutch, and all kinds of global styles of the past—and Warren Dykeman’s work, for example. I like making leaps between artists in these different camps.

A lot of these artists’ work has only received attention regionally, so I am really glad to present their work alongside artists who have more of an international following as well.

GKA: How will Indie Folk continue in your work and research?

MF: I’m interested in the idea of the rural these days. I think it has to do with where I'm living, in central Pennsylvania, which is very rural. The rural connects to a certain socioeconomic group—in fact a lot of the artists in this show are from working class families and grew up in small towns. Some of them are self-taught and didn’t go to art school, and I think that it’s an important part of leveling the playing field in the art world now.