Indie Folk: New Art from the Pacific Northwest

Brian Beck, Marita Dingus, Warren Dykeman, Joe Feddersen, Gaylen Hansen, Sky Hopinka, Denzil Hurley, Jessica Jackson Hutchins, Johanna Jackson, Chris Johanson, Eirik Johnson, D.E. May, Jeffry Mitchell, Blair Saxon-Hill, Whiting Tennis, Cappy Thompson, Joey Veltkamp

Online May 8-June 13, 2020

Curated by Melissa E. Feldman

The Pacific Northwest is home to a unique artistic ecosystem involving craft traditions, pre-industrial cultures, and Indigenous and pioneer histories. Like folk art, the works of the seventeen artists featured here are handmade, simple, and often blur the line between functionality and aesthetics. Artisanal woven baskets and tooled-wood objects mix with works that are makeshift, improvisational, and often employ salvaged materials. For the artists—patchwork quilters and abstract painters alike—a rural and working class ethos of making do with what you have is as foundational as art history and studio technique.

The following texts on the works comprise multiple voices and sources including email exchanges, artists’ statements, and excerpts from existing publications. Another group of voices here is for listening; Portland’s Mississippi Records has put together a playlist of classic Indie Folk music, a sound born in the Pacific Northwest.

—Melissa E. Feldman

Play List by Mississippi Records

Indie Folk: A Conversation with Melissa Feldman and Grace Kook-Anderson

Frieze

Looking for Texture in Online Viewing Rooms

by Kyle Chayka

Notes

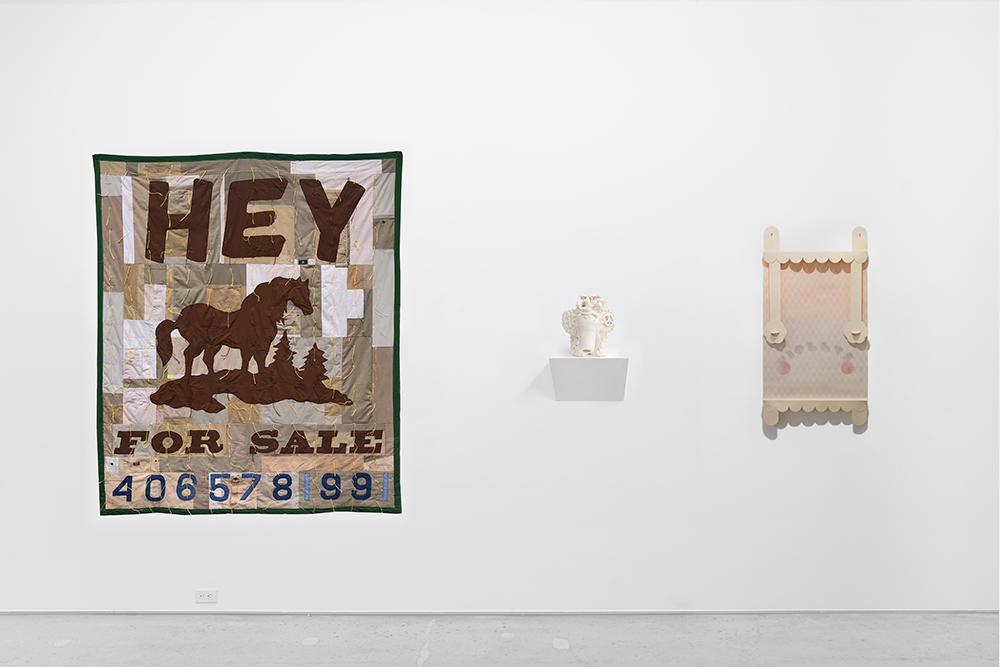

Installation

Works

Brian Beck

b. 1969; lives and works in Seattle, Washington

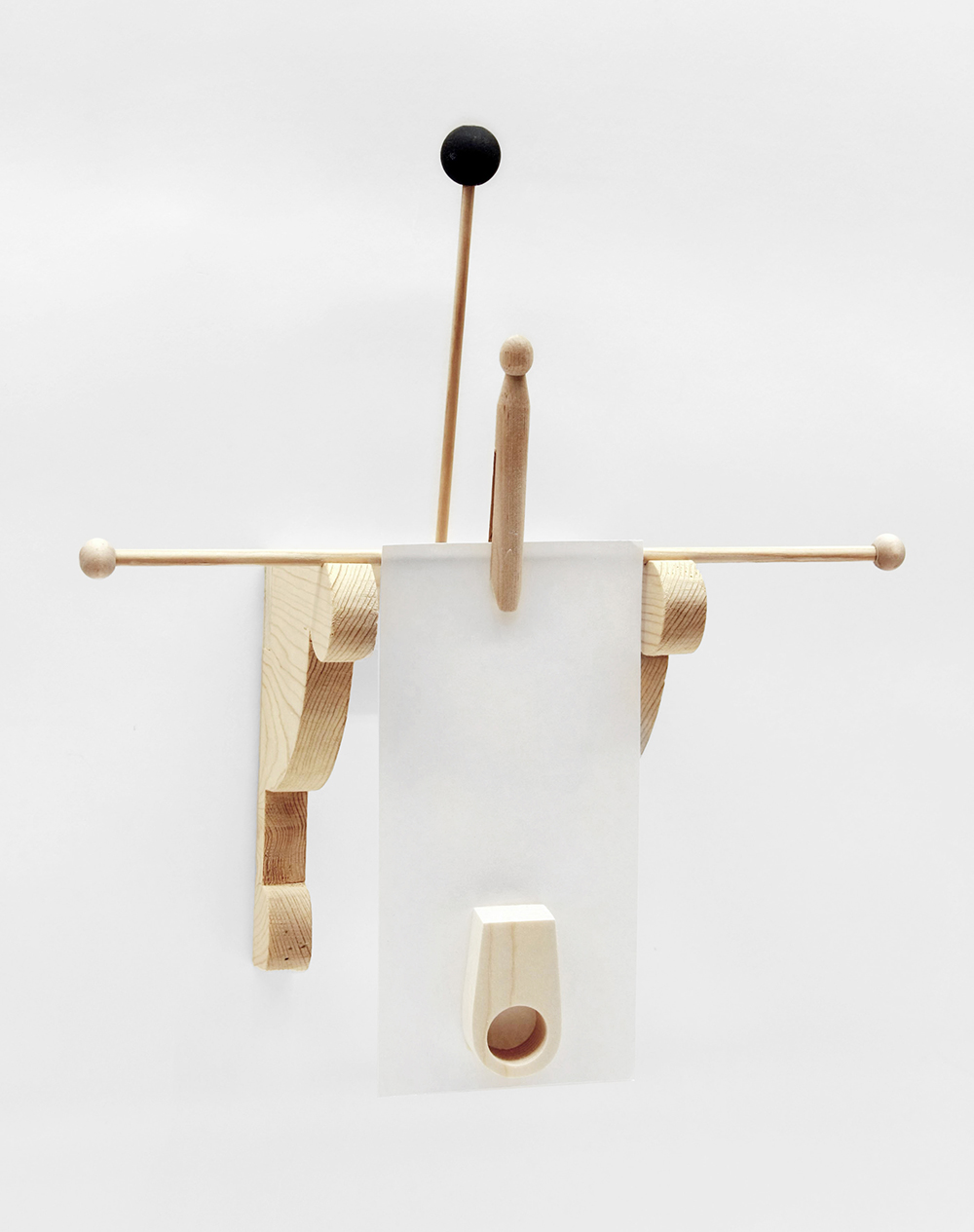

Brian Beck

Untitled (crow leaving barn), 2019

acrylic and enamel paint, wood

12 x 15 x 4 inches

Brian Beck

Untitled (crow over barn), 2018

acrylic and enamel paint, wood

21 x 9 x 11 inches

Brian Beck

Untitled (sheet and pin), n.d

acrylic and enamel paint, wood

12 x 15 x 4 inches

Beck can build a house—he lives in one he built—but prefers to make much smaller things like objects resembling traditional wooden toys, cuckoo clocks, and birdhouses. They are also made traditionally, with a set of antique German hand tools. Creating these charmingly surreal, flawlessly executed, yet deceptively simple vignettes involves nothing less than dovetail joints, German fretwork, and lathed Russian-type bergs. “Working this way,” Beck explains, “slows you down and makes you much more aware of the wood, and how things are going to fit together.”

The work is informed by his fascination with historic architecture and folk woodworking, northern European in particular. And while picking up on topics ranging from the pursuit of the black tulip, Norse mythology, and the logging industry, Beck’s creations ultimately come from the wide-open interior world of child’s play and the imagination.

—MF

Marita Dingus

b.1956; lives and works in Seattle, Washington

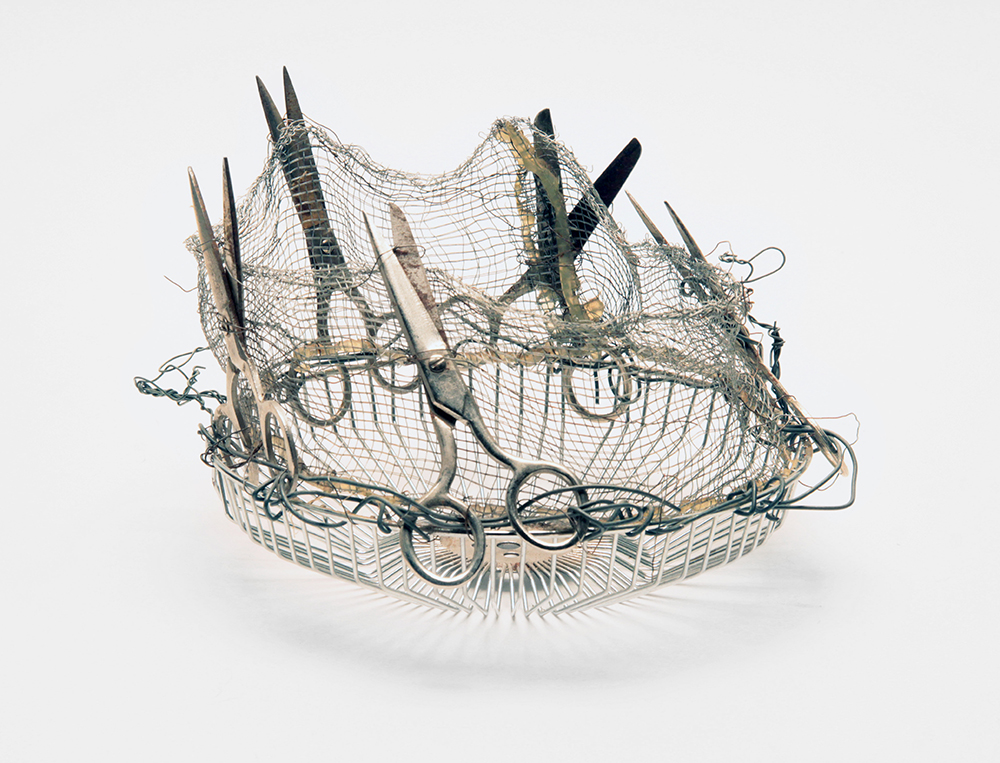

Marita Dingus

Silver Fence, 2003

pull tabs, wire

48 x 48 x 2 inches

Marita Dingus

Scissor Basket, 2003

scissors, metal

6 x 9 x 9 inches

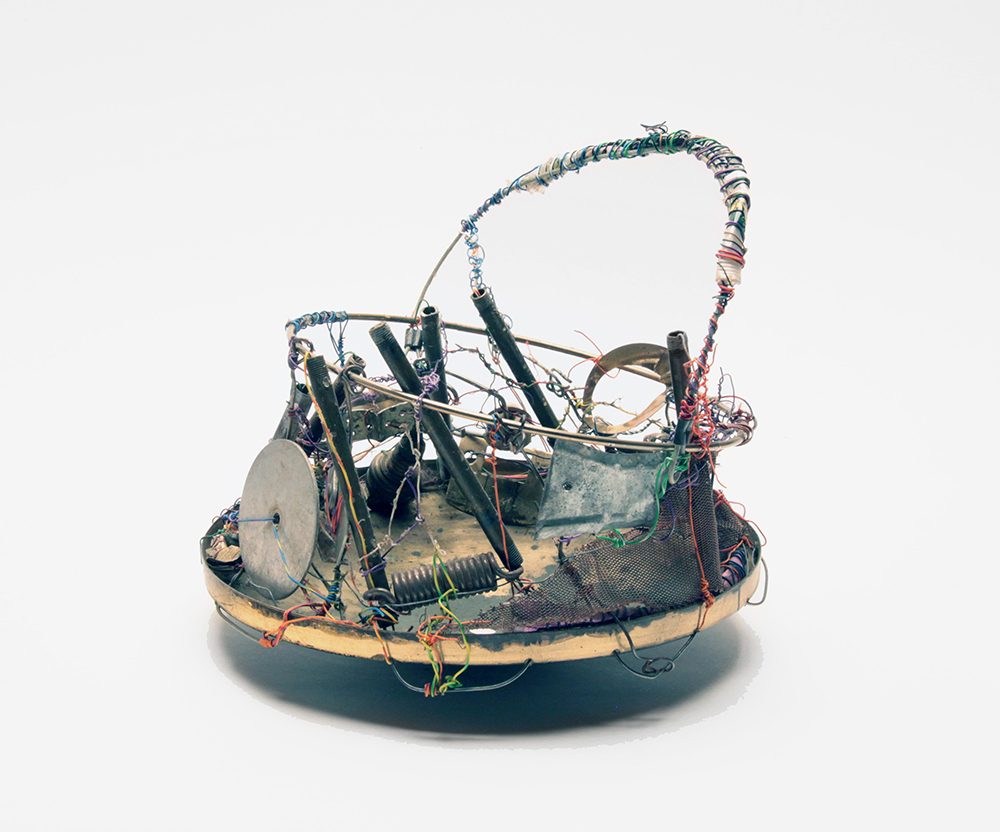

Marita Dingus

Fabric Basket, 2003

fabric, metal

18 x 20 x 20 inches

Marita Dingus

Metal Basket, 2003

mixed media

10 x 17 x 17 inches

Before heading to graduate school in the ’70s, Marita Dingus worked as road crew for the Washington State Department of Ecology. Soon the shards of rubber and metal she had picked up along the freeways would find their way into her work as sculptural assemblage, which was also informed by the Black Studies courses she petitioned to take in place of the usual Western art history classes. Intent on bringing African art and cultural traditions into contemporary conversations. Dingus’s doll-like figures (which can be giant-sized), baskets, and hand-tied nets she refers to as “fences,” connect racial with environmental issues, both subjects of ongoing abuse by Western industrialized corporate culture. The energy emanating from telephone wire, old clothes, bottle corks, machine parts, and other cast-offs spun into sculpture bring to mind African power figures and a tradition of wrapping things from turbaned heads and babies to small cloth-bound Vodun charms carried to ward off danger.

—MF

Warren Dykeman

b. 1967; lives and works in Seattle, Washington

Warren Dykeman

16 KON, 2019

acrylic and graphite on muslin

43 x 70 inches

Warren Dykeman

Aztek Dress, 2016

acrylic and graphite on Tyvek

22 x 30 inches

Warren Dykeman

Lago, 2019

acrylic and graphite on muslin

33 x 51 inches

Dykeman’s day job in commercial design carries over to his after-hours art practice in the typefaces, logo-like iconography, and road-sign graphics that fill his paintings, drawings, and objects. But the two are night and day in terms of messaging: clear and concrete versus opaque, impenetrable, and surreal. At the same time, there is a strong affinity with “the awkwardness of folk art,” he says, and the boldness of Northwest Coast Indigenous art as well as the work of contemporary artists he admires such as Jacob Lawrence, Faye Jones, Bill Traylor, and Keith Haring.

—MF

Joe Feddersen

(Colville Confederated Tribes)

b. 1953; lives and works in Omak, Washington

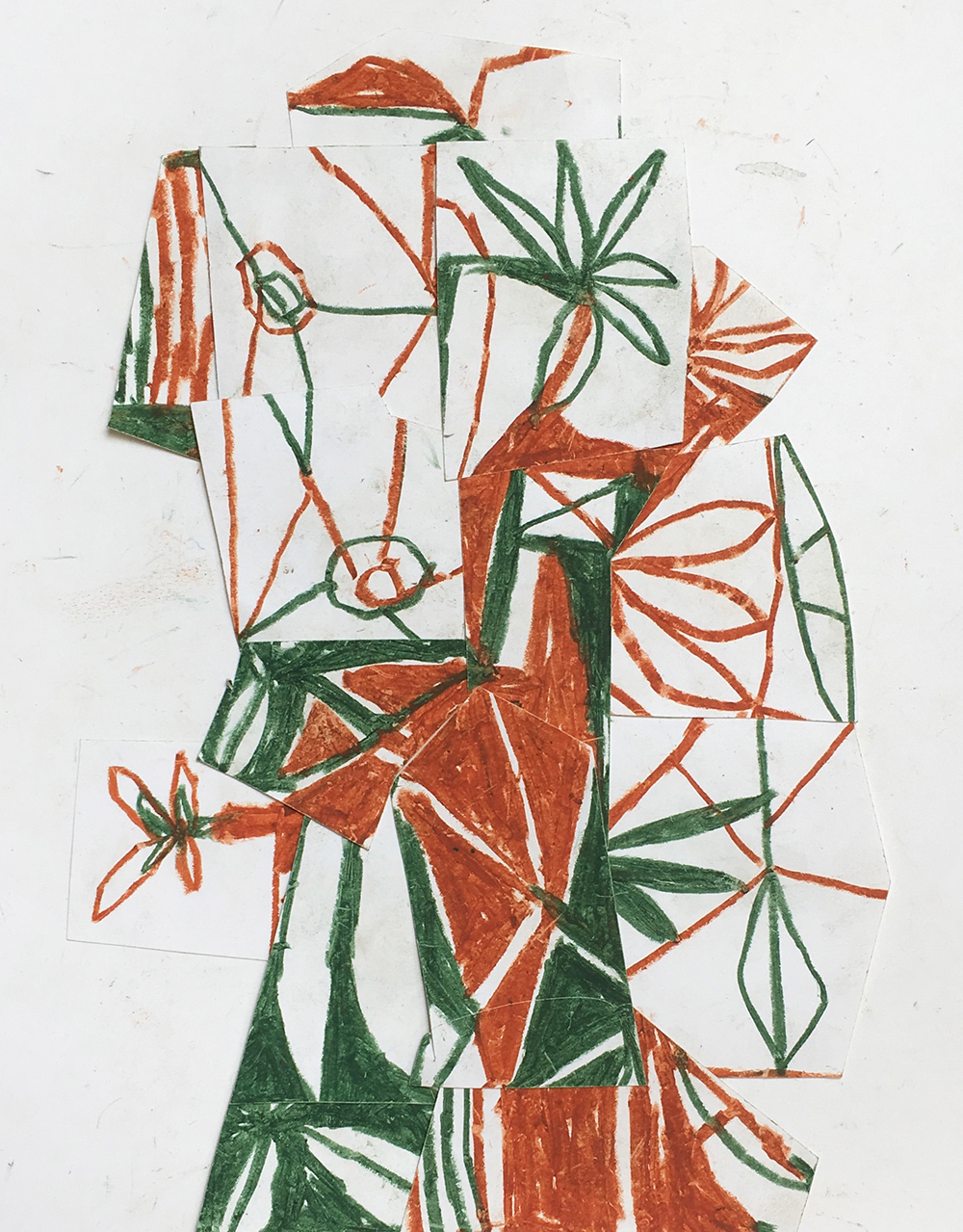

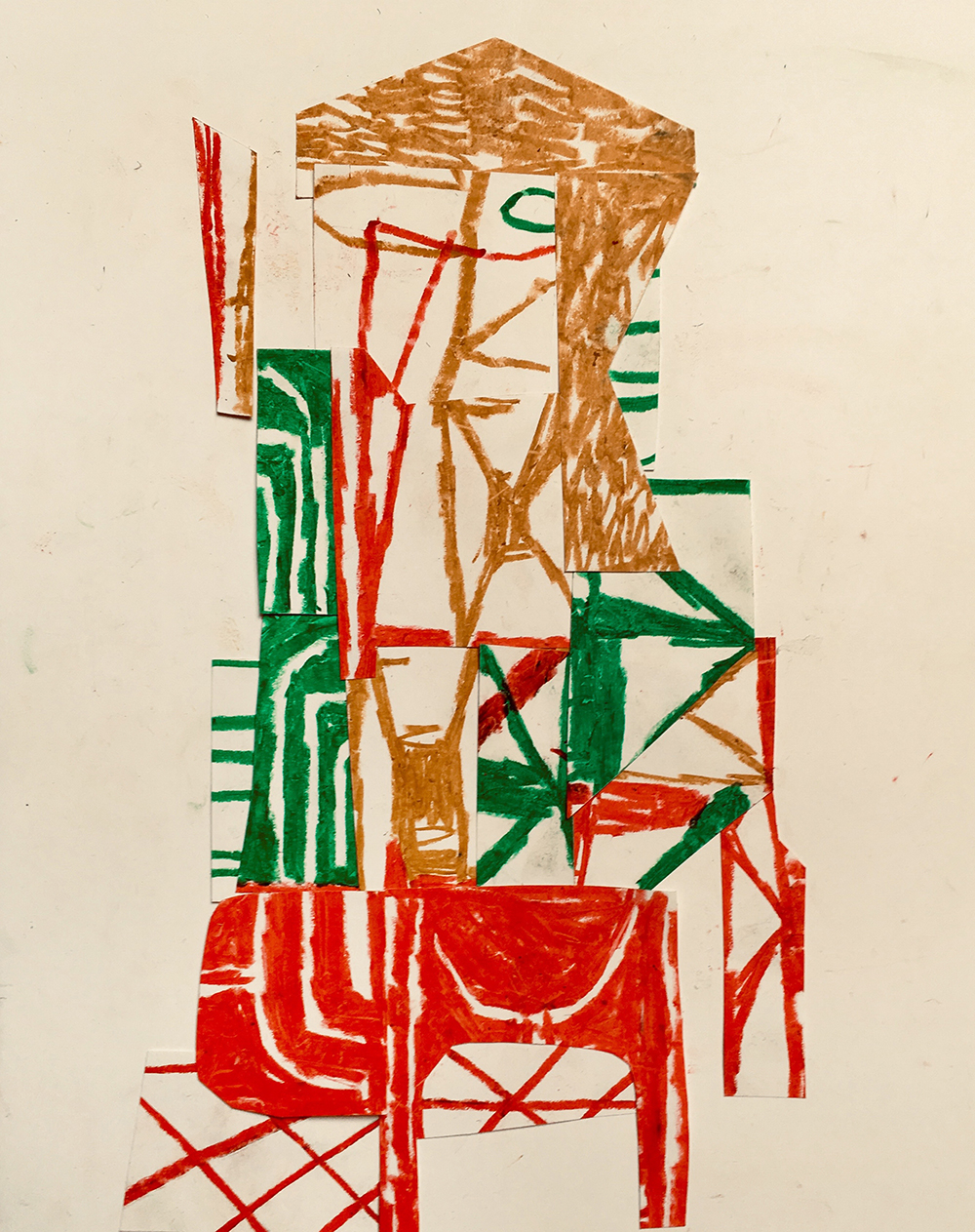

Joe Feddersen

Auntie's Flowers, 2018

monoprint with spray paint, relief, collage

18 x 24 inches

Joe Feddersen

Floating By, 2016

monoprint with spray paint, relief, collage

30 x 22 inches

Joe Feddersen

Roll Call, 2016

twined waxed linen

6 3/4 x 5 x 5 inches

Joe Feddersen

High-Voltage Tower, 2015

waxed linen basket

9 x 6 x 6 inches

Traditional Indigenous (Columbia Plateau, specifically) and contemporary Western imagery coexist surprisingly peacefully in the work of this Okanagan and Lakes artist of the Inland Columbia Plateau. Electrical pylons make convincing stand-ins for traditional geometric basket designs, while a hand-colored monoprint features a petroglyphic canoe making its way in a sea of DayGlo-colored, spray-painted graffiti. In a basket titled Roll Call (2016), the lineup of figures appears as inspired by Pac Man computer graphics as they are by the eagle- and wolf-headed hybrids of Indigenous origin stories. Whether suggesting the assembly line, the classroom, or the annual Parade of Pets in Olympia, WA (which is what the artist had in mind), the imagery seems at odds with the meditative action of basket weaving.

—MF

Gaylen Hansen

b. 1921; lives and works in Palouse, Washington

Gaylen Hansen

Man Bent Over with Tie, n.d.

oil on paper

30 x 44 inches

Gaylen Hansen

White Fish and Blue Glove, 2019

acrylic on canvas

48 x 60 inches

Gaylen Hansen

Kernal and Red Grasshopper, 2018

acrylic on canvas

36 x 72 inches

"The move outside of town onto ten acres and into an old log house caused my work to change in character, though the earlier concepts still were active. The place has the character of an island, a separate and separated entity, relating to the fantasy I had developed of Old Fort Bentleg. . .The psychology of separation and the rustic and country feel of the place slanted my work toward a kind of folk or primitive appearance." "Kernal Bentleg," one of the few select images which have surfaced in Hansen's paintings, must be taken as a direct autobiographical prototype. The "attributes" of this character—whiskers, hat, corn cob pipe, and boots—are unmistakable. His adaptation to a generalized schema built up of simple profile forms, is commensurate with the figures in Egyptian pictographs. . .These same honest and simple renderings, for instance in Riding Kernal and Falling Fish, recall nineteenth century examples of folk painting and sculpture, whereas the bold, brightly colored forms in Chicken and Compost with Tulips bring to mind a more child-like approach.

—from Kathleen Thomas in Sustained Visions (New York: The New Museum, 1979), 7.

Sky Hopinka (Ho-Chunk/Pechanga)

b. 1984; lives and works in Hudson, New YorkSky Hopinka

Lore, 2019

Total run time: 10:16

16mm to HD video, stereo, color

POR

Images of friends and landscapes are cut, fragmented, and reassembled on an overhead projector as hands guide their shape and construction in this film stemming from Hollis Frampton’s “Nostalgia”. The voice tells a story about a not too distant past, a not too distant ruin, with traces of nostalgia articulated in terms of lore; knowledge and memory passed down and shared not from wistful loss, but as a pastiche of rumination, reproduction, and creation.

—Hopinka on Lore from the artist’s website

Rebecca Sutton: How do you think modern video techniques can create new meanings and interpretations for this ancient body of story and history that informs your work?

Sky Hopinka: I think everyone [in film] is trying to figure that out, whether they're Native or white or from wherever. A lot of stories that are in popular culture are old stories. While we have foundational understandings of how to relate to myth, it's still something that is in constant conversation. How do we negotiate these technologies and how do we make them a part of our daily lives in a way that is meaningful to the past, but at the same time relevant for the future? It's a challenge, especially with indigenous stories or any sort of people that have been affected by colonization. Their culture and our culture and their history and our history have been romanticized or treated as lost—[as if] it’s gone and it's been gone for hundreds of years and it's not what it was. But that's an outsider imposition as to what these cultures are and how they exist.

— Interview with Rebecca Sutton, NEA Art Works Blog, 11/16/18 https://www.arts.gov/art-works/2018/art-talk-filmmaker-sky-hopinka

Denzil Hurley

b. 1949; lives and works in Seattle, Washington

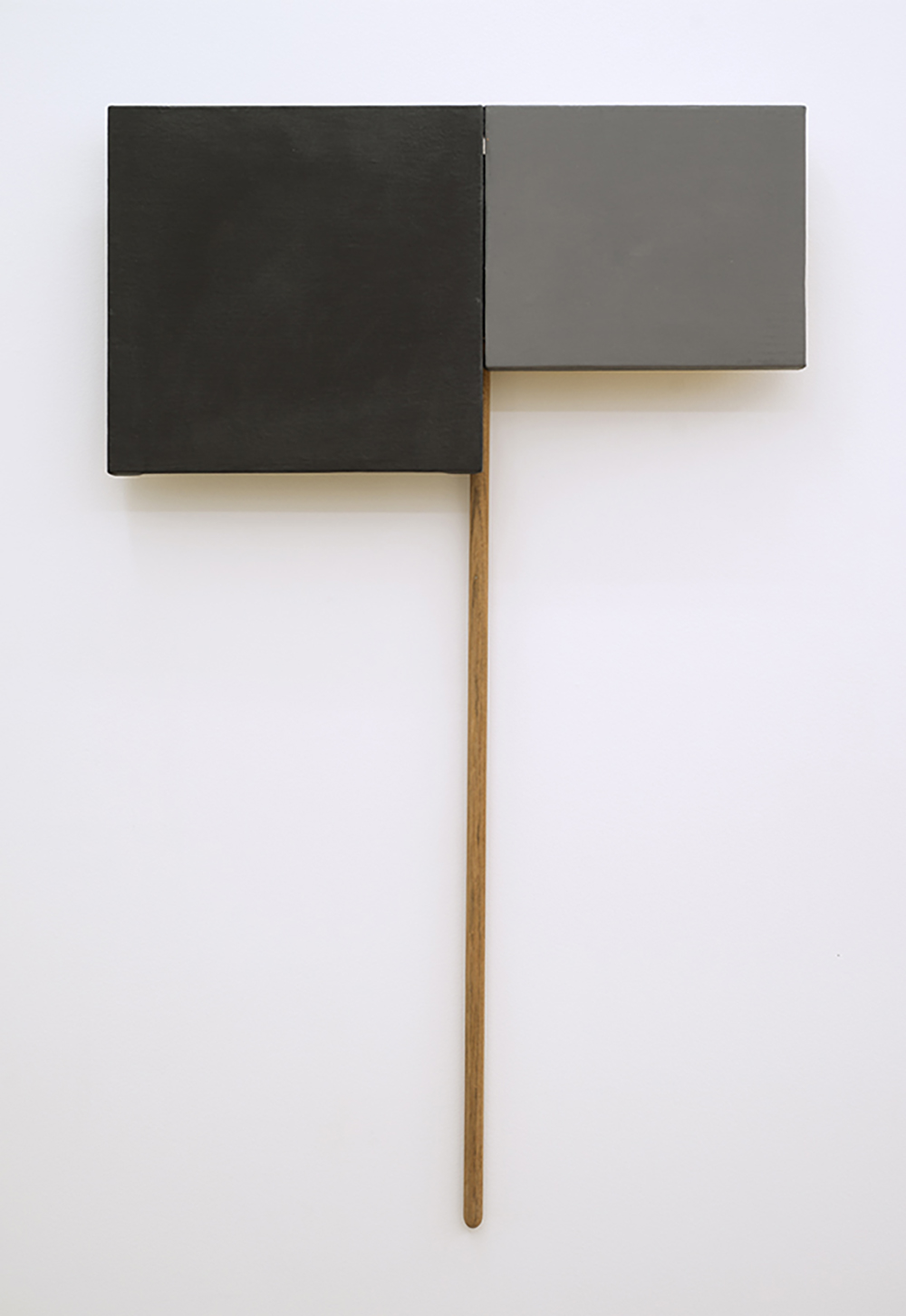

Denzil Hurley

Coupled Glyph #1, 2016

oil on linen with brown stick attachment

50 x 26 inches

Denzil Hurley

Strip Glyph #1, 2019

oil on linen

28 1/2 x 19 1/2 x 1 1/2 inches

Denzil Hurley

Slat Glyph, 2016

oil on linen

14 x 21 1/2 inches

The addition of a stick or line to the paintings implies an assertion, an action, a grievance, or a tool of ambiguous utility. The “signs” are often fused together and allude to a form of communal usage. Hurley has fashioned other paintings into “windows” and “frames” that become passages to engage the wall behind the paintings. By means of limiting his vocabulary and using stripped down forms as dynamic metaphors, Hurley’s project is linked with the trajectory of painter Kazimir Malevich and his socially progressive formal experiments. In the way that Malevich fused painting with the ambitious realities of his times, Hurley manages to convey the optimism and darkness of today.

— From the press release for Take a stick to it, put it on a line, solo exhibition at Canada, New York, September 2016.

"I thought of your work for the show because your paintings look hand-constructed—not always, but often enough—and because of how the shapes and scale of the work bring to mind things like fences and window frames (homemade not Home Depot). I see the use of the broomsticks as tying into the utilitarian aspect of folk art. There is also what I am interpreting as a "folk" reference to island culture of Barbados, if that's a source for the makeshift look."

—Email from Melissa Feldman to the artist, April 14, 2020.

Jessica Jackson Hutchins

b. 1971; lives and works in Portland, Oregon

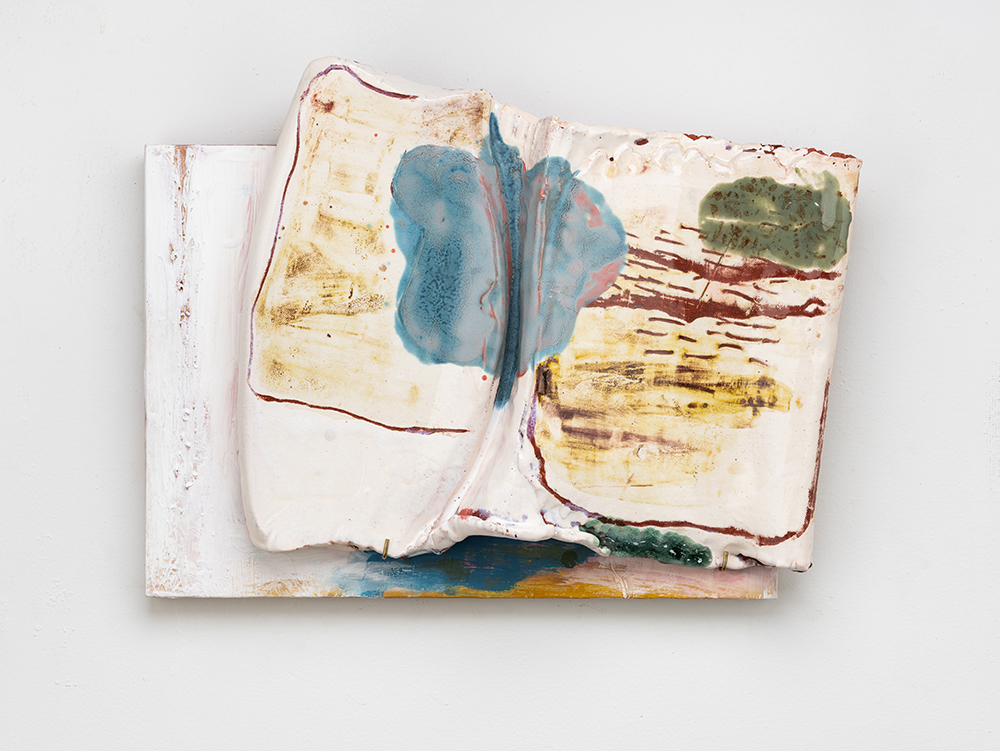

Jessica Jackson Hutchins

Butterfly Kiss, 2019

flashe and acrylic and wood stain on board with glazed ceramic

11 3/4 x 15 1/2 x 2 3/4 inches

Jessica Jackson Hutchins’

Cloud, 2019

glazed ceramic, fused glass

15 x 12 x 3 inches

Jackson Hutchins wanted a change from painting and started working with clay in 2005, shortly after moving to Portland. Gradually the clay took over, leading to the bulky, sprawling furniture-sculptures that have come to characterize her practice. Her newer wall-mounted, ceramic abstractions appear as intimate snapshots from her personal domestic space. Delicate and painting-like, the pieces capture the small scenes and moments—a quiet cup of coffee, a book to read, blades of grass bending in the breeze. Plus pictures on the wall are domestic, too.

—MF

Johanna Jackson

b. 1972; lives and works in Portland, Oregon

Johanna Jackson

Untitled, 2018

glazed porcelain

4 x 5 x 5 inches

Johanna Jackson

White porcelain teapot more handle than spout with soft glaze and drawing marks, 2020

4 x 9 x 5 inches

glazed porcelain

Johanna Jackson

Porcelain Vase Filled with Drawing, Black Smears and Square Fruit, 2019

glazed porcelain

9 1/2 x 8 1/4 inches

Office Magazine: How does this installation reflect your actual living space?

Johanna Jackson: I mean, this is our actual living space. These are our cups. It’s hard to part with them. That was my special cup.

Chris Johanson: Yeah, we were using these just before we left.

OM: I can’t even imagine learning all these mediums. What did you start with?

JJ: Well, it was basic need. We got this place in Silver Lake that’s at the top of 120 outdoor steps, and we didn’t feel like carrying a bunch of furniture up them. So we started make it there. Also the economic aspect of things, being working people, we just couldn’t afford things.

CJ: We just have to make everything.

JJ: We get to make everything.

—Interview above from: http://officemagazine.net/chris-johanson-x-johanna-jackson-middle-riddle

Chris Johanson

b. 1968; lives and works in Portland, Oregon

Chris Johanson

Then, 2020

acrylic on recycled paper

8 1/2 x 11 inches

Chris Johanson

Within Time (With Connectivity and Isolation) Are We, 2020

acrylic on recycled paper

19 15/16 x 24 3/4 inches

The paper is from Christopher Garrett Studio that was in Brendan Fowler’s Studio in LA, they lost almost everything in a fire there. That paper was water damaged so Christopher didn’t want it anymore. In addition to the blank paper, he was also throwing away all these works on paper. I convinced him to let me store his drawings which are now in my studio here in Portland with little smoky water damaged energy in them.

—as told to Amy Adams, May 5, 2020

Eirik Johnson

b.1974, lives and works in Seattle, Washington

Eirik Johnson

Scrapped Train, Arlington, Washington, 2006

archival pigment print

24 x 30 inches

edition of 10

Eirik Johnson

Art of Wood Store, North Bend, Oregon, 2006

archival pigment print

24 x 30 inches

edition of 10

Eirik Johnson

The Road to Forks, Washington, 2006

archival pigment print

24 x 30 inches

edition of 10

$3,500

Eirik Johnson

Old Photographs, Seaport Lumber, South Bend, Washington, 2007

archival pigment print

30 x 24 inches

edition of 10

Eirik Johnson

Destruction Island, off the Coast of Washington, 2007

archival pigment print

24 x 30 inches

edition of 10

“Sawdust and pitch—these two scents bind me inextricably to the logging days of my childhood on the Olympic Peninsula in Washington State. Sawdust from my father’s chainsaw sprayed out like a particulate blood-sign of tree-flesh. Chainsaw noise ripped through the greater silence of the forest. Trees, I felt sure at the time, never meant to speak so nakedly aloud in what, as a child, I took for pain. Nor, in their lashing down, had I ever seen anything so violent as their boughs whipping and thrashing the earth in frenzy.”

—excerpted from Tess Gallagher, “After the Chainsaws: The Alchemy of Restoration,” Eirik Johnson: Sawdust Mountain (New York: Aperture, 2009)

D.E. May

1952 -2019; Salem, Oregon

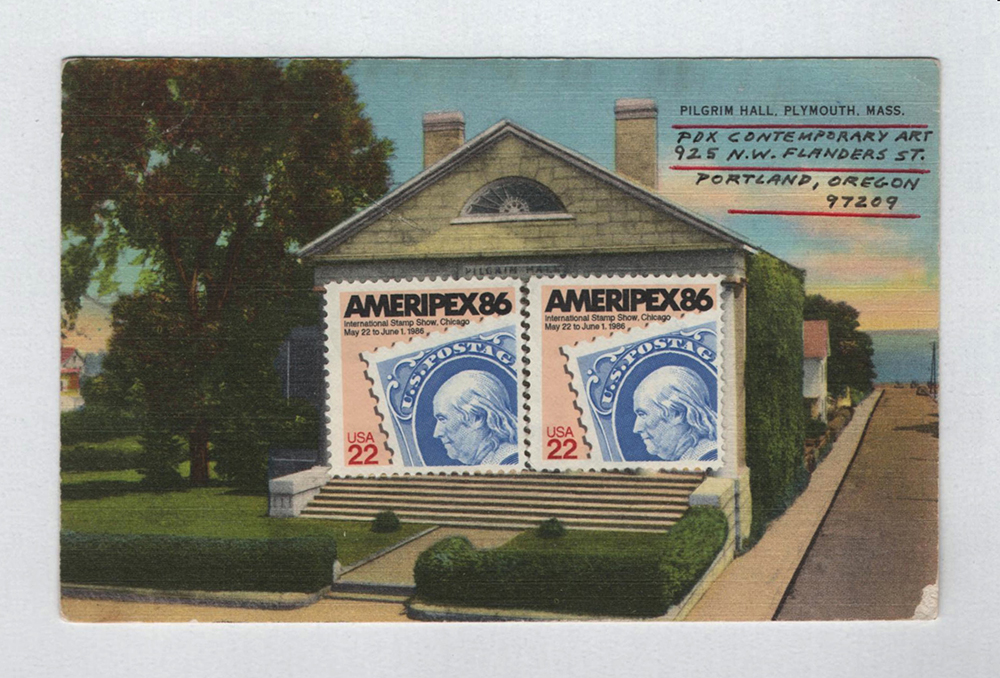

D.E. May

Untitled, 2015

graphite, colored pencil and ink on found postcard

3 1/2 x 5 3/8 inches

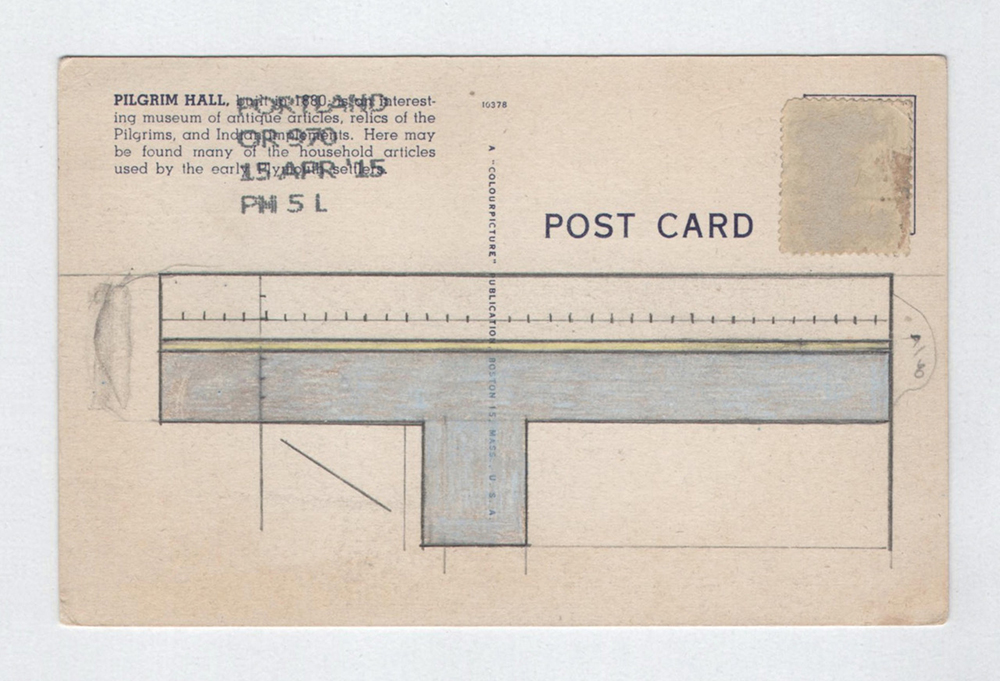

D.E. May

Untitled, 2006

mixed media

5 7/8 x 4 inches

D.E. May

Untitled #273, 2019

ink, gouache, found papers, tape and graphite on cardboard

7 1/4 x 5 x 1 3/4 inches

Out of financial necessity as well as aesthetic preference, D.E. May made his assemblages and drawings using wood scrap and stashes of vintage papers found in local junk shops. In his work room—the term he preferred over “studio”—old composition and ledger paper, stereograph cards, used and unused stamps, and other unidentifiable flotsam were sorted and stored in cubbies and drawers.

There is the sense that May would have liked to make useful things with these useful, if dated, materials. For instance, his postcard drawings, festooned with both decorative and functional stamps, were actual correspondence sent through the mail. The geometric drawings look technical; the sculptures resemble architectural models. But despite these appearances, May's mailroom-like work space, the office and school supplies he used, and task-oriented approach, what he produced is not utilitarian in the least.

—MF

Jeffry Mitchell

b. 1958; lives and works in Olympia, Washington

Jeffry Mitchell

Elefant Candle Stick, 2019

glazed ceramic

12 1/2 x 10 1/2 x 14 inches

Jeffry Mitchell

Poster #5 Violet with Additions, 2016

acrylic on paper

44 x 24 x 2 1/2 inches

Texting with Jeffry last week, I learned that his signature elephants do not come from the French children’s book character Babar, as I had thought, but Disney’s Dumbo. The scallop edging on his bandsaw-cut wood furniture, ceramic platters, and paper “posters” are also inspired by Disney’s stylized world . “The scallop,” he wrote, “is Swiss chalet—Heidi’s—the seven dwarves’ cottage, Gepetto’s workshop, and Scandinavian folk furniture.” That makes sense when you think of popular culture as a kind of post-industrial folk. He was working on a new set of alphabet dishes (settings for twenty-six) and told me about being from a family of eleven. “The house was a perpetual nursery.”

Blair Saxon-Hill

b. 1979, lives and works in Portland, Oregon

Blair Saxon-Hill

With All That Is Near, 2018

wood, found paint strainer, foam, fiber reinforced plaster, cement, cloth, foam, metal, gouache, pigment

69 x 23 x 1 inches

Blair Saxon-Hill

Bears and Beckons, 2018

wood, reversed handy work, mesh bag, incomplete embroidery, gouache, cement, fiber reinforce plaster, found plastic strapping; wood, gouache, fiber reinforced plaster, cement, found plastic shard, lava glaze bead, basket shard

67 x 53 x 10 inches

Blair Saxon-Hill

On Deck, 2018

LA metal, wash cloth, tin can, railing element, wood, rain jacket, fiber reinforced plaster, gouache, foam

84 x 48 x 8 inches

Notes from telephone conversation with the artist, April 5, 2020

“Deeply rooted in NW aesthetic” but her work hasn’t been seen in that context.

Scarcity of basic painting materials in PNW even now -- making do approach with roots in both hippy and rural culture

Significant letterpress movement, also papermaking

Studio (since 2007) is near train tracks and giant homeless population and shelter. Walks tracks and gathers materials and notices how people make things from nothing. “I like things that have history, that can be multivalent, and that I can pervert.”

Pieces are like puppets brought to life when installed -- scenarios for her cast of characters.

Importance of the long materials list and word choice in descriptions of work; e.g. “hanky” (queer) vs. “hankerchief” (‘50s housewife).

Contemporary Russian craft book – important source. Re: hard times/no supplies after collapse of Soviet Union and how people jerry rigged things they needed from stuff around the house.

"As an artist, I act as a researcher, a wanderer, a hunter, an irreverent butcher, a matchmaker, a gambler, and a psychic. I respond to this remarkable world by collecting from its deep pools of value and disregard, with the aim of sincerely reformulating the bizarre, subtle, elegant, broken, and in love to focus on the humanity of our time in this grotesque political climate."

—excerpt from 2018 artist statement

Whiting Tennis

b. 1959, lives and works in Seattle, Washington

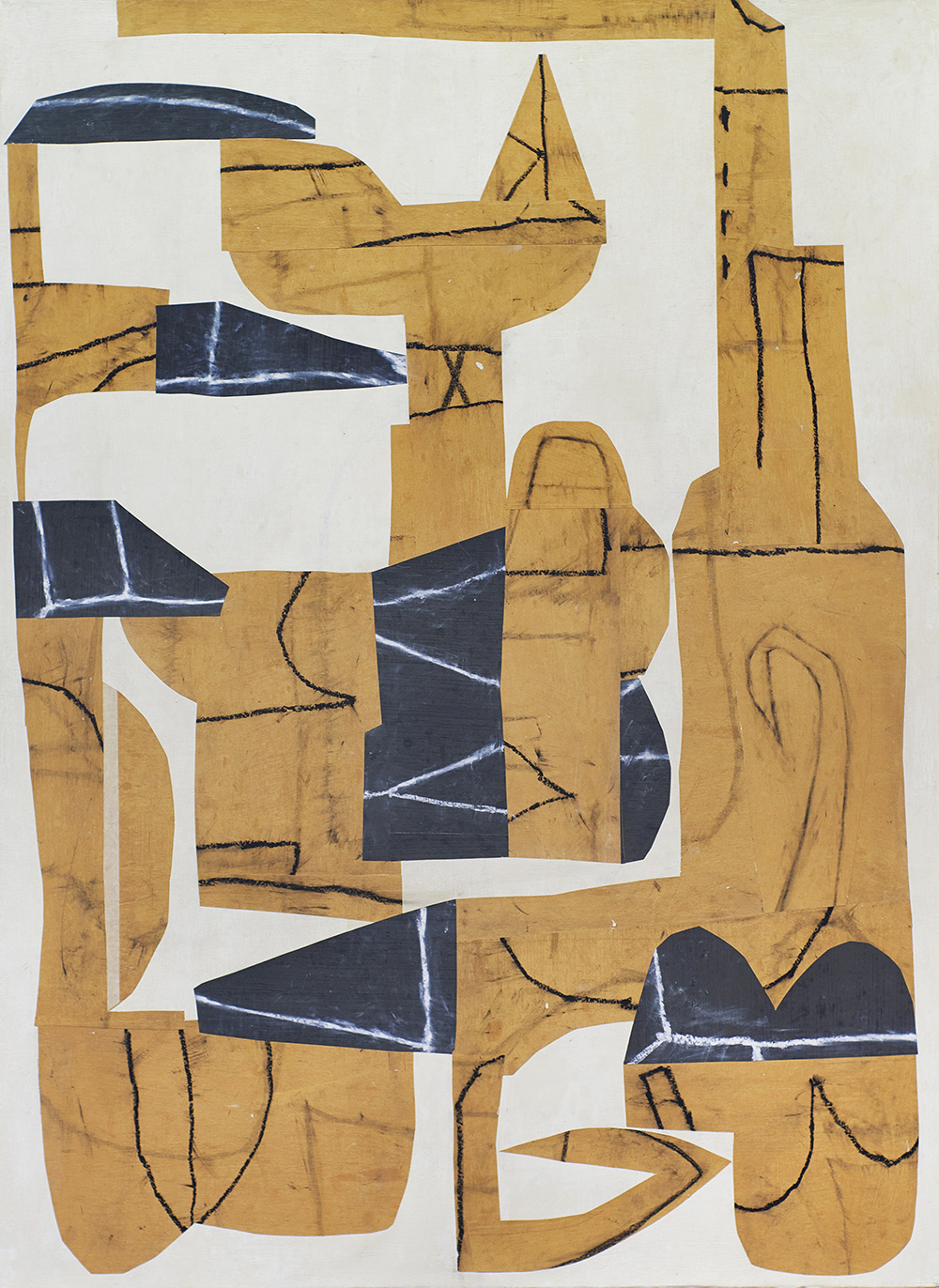

Whiting Tennis

Feral Cat, 2019

acrylic with collage, hand-printed paper and oil pastel on canvas

45 x 33 inches

Whiting Tennis

Untitled, 2018

oil pastel and collage on hand printed paper

18 x 9 inches

Whiting Tennis

Tree in Green and Ochre, 2019

oil pastel and collage on paper

20 x 14 inches

Whiting Tennis

St. Nic, 2019

oil pastel and collage on paper

22 x 13 inches

Seattle-based artist Whiting Tennis finds inspiration in the timeworn, provisional structures that populate the rural Northwest. Drawing grounds his practice, providing a starting point for his idiosyncratic forms that often combine paint with woodblock prints cut to reference the surface texture of plywood, tree bark, or shingles. From a paint-splattered blue tarp to a pieced-together shed, Tennis’s art celebrates the everyday materials and eccentric forms of often-overlooked objects. His work also incorporates repurposed materials, such as discarded wood, cardboard, concrete, plaster, paint, asphalt, and tar. Each work revels in the mystery and layers of usage embedded within them.

— From the exhibition text for Opener 22: Whiting Tennis at the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery, September–December 2011

Cappy Thompson

b. 1952; lives and works in Seattle, Washington

Cappy Thompson

Blue Tree Keeper, 2015

vitreous enamel reverse-painted on blown glass

11 x 10 x 6 inches

Cappy Thompson

Beekeeper, 2015

vitreous enamel reverse-painted on blown glass

11 x 9 x 7 inches

Cappy Thompson

Guardian Angels, 2015

vitreous enamel reverse-painted on blown glass

15 x 11 x 5 inches

For me, as a narrative painter, the issue has always been content. The issue wasn’t glass, the material that I chose some thirty-seven years ago. Nor was it the painting technique—grisaille or gray-tonal painting—that I taught myself to use.

Early in my career I was drawn to the images, symbols, and painting of the medieval period—but not just the Christian tradition of Western Europe. I loved the content of Hindu, Pagan, Judaic, Buddhist, and Islamic painting as well. What I loved was the naïve naturalism and devout simplicity of the pre-modern—like the folk art of any period.

—artist statement from Traver Gallery website

Joey Veltkamp

b. 1972; lives and works in Bremerton, Washington

Joey Veltkamp

The Blue Angels, 2018

fabric, thread

72 x 91 inches

Joey Veltkamp

Washington State Ferries, 2018

fabric, batting and thread

102 x 90 inches

Joey Veltkamp

Hey! (gay horse), 2018

work pants, fabric, and embroidery floss

80 x 93 inches

Melissa E. Feldman: You mention “work pants” in the list of mediums for Hey! Is that dress code for queer?

Joey Veltkamp: "Work pants" in this case refers to the juxtaposition (my work frequently deals in contrast) of high and low. The work pants are both Carhartt-style ranch or construction clothes, plus Dockers/khakis favored by Seattle tech bros in the ’90s. On the other hand, the cowboy aspect definitely lends itself to homoerotic themes.

MF: About the ferries piece—how did you select the names? Did you pick only Indigenous ones or are those all the ferry names?

JV: They are the names of retired ferries I pulled from the Washington State Ferries wikipedia page. This is all from memory but I know it's out there somewhere. The way the ferries are named is that the WSF solicits suggestions from the public. But with only two exceptions (Evergreen State/Rhododendron) they always wind up using tribal names. I think I recall reading that several ferry routes follow the same routes that indigenous people—the original navigators of the Salish Sea—have been using for centuries.

MF: In Blue Angels, I like how you make the flags the main event and the planes are just a cluster of small white streaks. You seem to focus on the weird patriotism of that event,which always struck me as out of character for the Pacific Northwest. I'm including it in the show because I see Betsey Ross’s American flag as a popular folk symbol.

JV: Yes, I couldn't agree more that it seems so out of character for folks in Seattle to love the Blue Angels. Technically, I call this piece, "Fuck the Blue Angels!" but since my son loves the Blue Angels so dang much, I just called it Blue Angels. I couldn't hate them more. All the weird nationalism and flag waving and noise and violence. Gross.

—Email correspondence between Melissa Feldman and the artist, April 27-28, 2020

Brian Beck and Warren Dykeman, courtesy of studio e, Seattle.

Joe Feddersen, courtesy of Charles Froelick Gallery, Portland.

Gaylen Hansen, courtesy of Linda Hodges Gallery, Seattle.

Denzil Hurley, courtesy of CANADA, New York.

Jessica Jackson Hutchins, courtesy of Marianne Boesky, New York and Aspen.

Chris Johanson, courtesy of Altman Siegel, San Francisco.

Eirik Johnson, courtesy of G. Gibson Gallery, Seattle.

D.E. May and Jeffry Mitchell, courtesy of PDX CONTEMPORARY ART, Portland.

Blair Saxon-Hill, courtesy of Nino Mier, Los Angeles.

Joey Veltkamp and Whiting Tennis, courtesy of Greg Kucera Gallery, Seattle.

Cappy Thompon and Marita Dingus, courtesy of Traver Gallery, Seattle.

About the Curator

Along with her ongoing work as an independent curator and writer, Melissa E. Feldman held positions for the last several years as Distinguished Visiting Faculty at Cornish College of the Arts, Seattle, and Director of the Neddy Artist Awards. Recent exhibitions include Push Play, an Independent Curators International touring exhibition (2013-17); A Cool Breeze: L.A. and Vancouver Art in the 1960s and Beyond at Griffin Art Projects, Vancouver B.C. (2017); and the traveling exhibitions Another Minimalism: Art after California Light and Space (2015-16, with a catalogue) organized by the Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh, UK, and Dance Rehearsal: Karen Kilimnik’s World of Ballet and Theatre (2012, with a catalogue) organized by the Mills College Art Museum, Oakland. Feldman has been a frequent contributor to Art in America and Frieze and has also taught at the California College of Art, the San Francisco Art Institute, and Goldsmith’s College, London. Feldman is credited with organizing the first monographic exhibitions for Karen Kilimnik, Martin Kippenberger, and Hiroshi Sugimoto in the 1990s as a curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia.