Mariel Capanna

and Africanus Okokon

in conversation upon the occasion of Overlook, Capanna’s solo exhibition at Adams and Ollman.

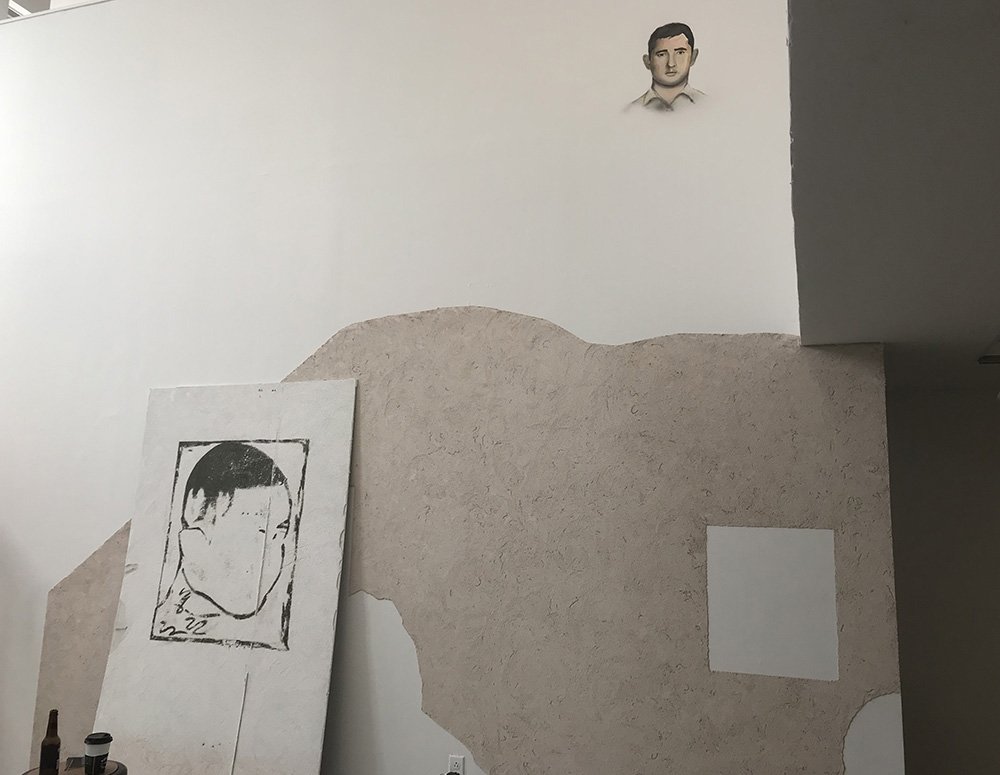

Mariel Capanna: I just scrolled back to see what I was doing this time last year and was happy to find that I was with you and José! We spent most of the week de-installing Home Vision Test1: unbuilding our temporary wall, rolling up your vinyl billboards, packing away the camera and projector, burying our mural with a few coats of Kilz Primer, scraping down and sweeping up lime plaster, wearing masks to ward off the dust, getting our coffee cups confused with little to no worries about germ-sharing with friends.

Bittersweet to bump into these odd iPhone snapshots of our project's deconstruction just a few weeks before lockdown. Here's one of my favorites (I wonder if you'll dig it as much as I do):

deinstallation image, Home Vision Test, February 2020, Yale School of Art. Photo: Mariel Capanna

deinstallation image, Home Vision Test, February 2020, Yale School of Art. Photo: Mariel CapannaWhile the three of us were dreaming up Home Vision Test, we spent a lot of time sitting on the futon in José's studio comparing our distinct but related feelings of intimacy with faraway people and places. One year later, I find myself hunkered down for covid-winter in Salt Lake City, UT, most of the way across the country from you (in New Haven, CT) and José (in Brooklyn, NY). I guess at this point, we all qualify as faraway people in faraway places in relation to one another.

Despite the distance, it's been easy to keep you two close. Your influence on my work and my thinking is so easy to spot (from where I sit, at least)!

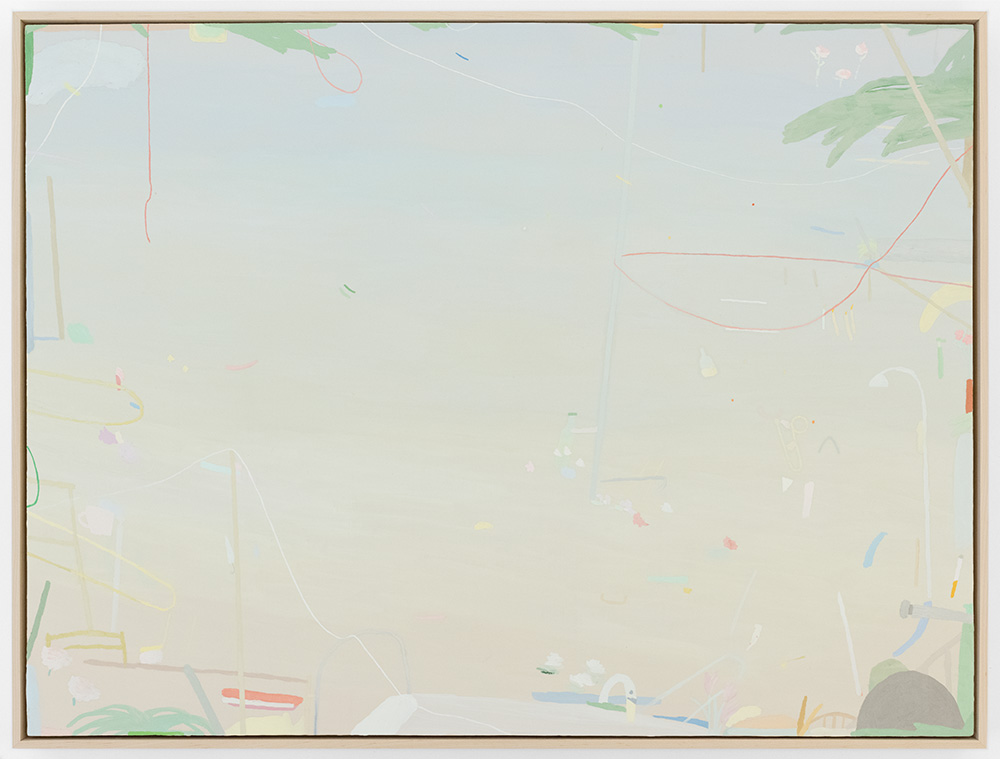

Mariel Capanna, Cigarette, Roses, String, Swan, 202, oil and marble dust on panel, 30 x 40 inches.

Mariel Capanna, Cigarette, Roses, String, Swan, 202, oil and marble dust on panel, 30 x 40 inches.An example: while I was working on Cigarette, Roses, String, Swan for my exhibition Overlook, I kept staring at this unfinished painting, wondering how I could bring it all together without overfilling the negative space or introducing too much visual weight. Then I was struck with what felt like a novel idea: to use thin, string-like shapes to loosely connect the disparate parts of the painting. While I was packing the work to ship to Portland, it occurred to me that this was a compositional trick I had absorbed from José's studio. All the ribbons and ropes and banners winding through his paintings last year seem to have hitched a ride with me to the mountain west.

José de Jesus Rodriguez, right foot up, left foot, fuck your couch, 2020, oil, acrylic and airbrush on canvas, 48 3/4 x 46 5/8 inches.

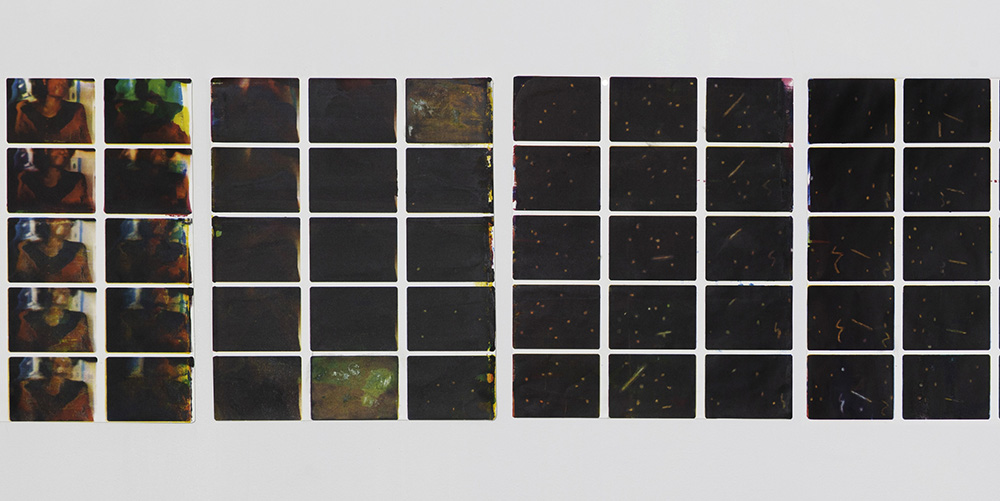

José de Jesus Rodriguez, right foot up, left foot, fuck your couch, 2020, oil, acrylic and airbrush on canvas, 48 3/4 x 46 5/8 inches.There's also a moment in your montage film .srt that has stuck with me. It's a second or two after the voice-to-text narrator says ". . . we might fill in some of those gaps," when these scratched flecks of warm light start darting around like startled bats in (or on or under) a dark/black space. That flickering movement—that lightness of weight and value—was at the front of my mind while painting for Overlook. I've been comforted to find that our collaborative relationship can live on, asynchronously, in these small but mighty ways.

Africanus Okokon, stills from .srt, 2019, performed hand-edited 16mm montage film, TRT 9:18.

Africanus Okokon, stills from .srt, 2019, performed hand-edited 16mm montage film, TRT 9:18.I wonder: Has anything stuck with you formally and/or thematically from Home Vision Test, one year later? When you're working alone in your studio, is there any aspect of your practice that still feels social/collaborative? And can you tell me about those flecks of light—how you think about them, how you made them?

Africanus Okokon: I'm not sure if collaborative is the right word, but there are definitely vestiges of Home Vision Test and of our creative relationship that continue to creep up in my work. I look at the work of yours from our installation that you gave me (plaster, printout on drywall?) almost every day, as it hangs above my fireplace which my girlfriend and I use as a shelf to display artwork and objects. I remember in our installation, Negative Shape was just that—an artwork on a shelf. It's somewhat of a centerpiece of my apartment, which is sort of funny because it was a bit of an afterthought in that installation.

Mariel Capanna, Negative Shape, 2019, lime plaster and inkjet print on drywall as installed in the home of Africanus Okokon.

Mariel Capanna, Negative Shape, 2019, lime plaster and inkjet print on drywall as installed in the home of Africanus Okokon.In both Home Vision Test and my apartment, its function is somewhat decorative (as art hanging on the wall usually is) but what I love about it is the anti-subject focal point. In the studio, I've been working on two almost identical paintings: one that features a shelf with decorative objects and one of the same images without the shelf or the decorative objects—almost like they are erased. I wouldn't be surprised if your painting sparked that idea.

It's interesting that you bring up the specks of light. I use different techniques to achieve that depending on the material I am animating on, but the process is essentially this: I attempt to follow a small mark in animation across the frame until I forget/lose track of/am confused by where it is. When I lose track of where the mark is (this happens when I have many of them at once), I start the process again from the first frame until the frames are crowded with moving and disappearing parts. I’ll add that I'm influenced by a long line of cameraless and experimental animators like Stan Brakhage, Len Lye, Oskar Fischinger, John Whitney, Stuart Hilton and many others.

Africanus Okokon, select frames for Verbatim Loop, 2019, silkscreen on paper.

Africanus Okokon, select frames for Verbatim Loop, 2019, silkscreen on paper.It reminds me of how your process is described in Overlook, as an attempt to capture imagery as it moves off-screen or into the next scene but recorded in fragmentation. This makes me wonder, what types of films/documentaries/moving image works are you working from when you make these works? How do you know when one will make it into a painting? Do you make sketches beforehand or while watching?

MC: I'm glad you reminded me of Negative Shape. The paintings in Overlook are so different from that in terms of color, mood, and materials, but I think that the vacant focal point you mentioned is something they all have in common. It's as if each painting is missing a protagonist, filled instead with empty space, or with light-weight peripheral things of equal and small importance.

The disorientation, the forgetting, the losing-track-of-things involved in your process of hand-animating film cells resonate with me, bigtime. When I paint from movies, I watch the screen until some color or shape in-frame catches my eye, then I turn toward my palette to find or mix that color, then I turn toward my painting to jot down that shape. In all the time that I'm paint-mixing and brush-wielding, I'm necessarily missing many minutes of footage, which means that, inevitably, I'm also missing dozens of visual treasures that I could have otherwise caught and collected. This odd process forces me to accept all the losses that I associate with divided attention. When I look at my finished paintings, of course, I see what's there—the moments that I managed to spot and jot down—but I also see what's not there, what I failed to catch. I see the amorphous, fuzzy-edged shape of all that I missed when I chose to look the other way.

As for my source materials, at this point, the ratio is about 3:1, from documentary footage to fiction films. I used to be very strict with self-imposed time constraints: I could only watch one film per painting, no pauses, and the work was necessarily finished when the closing credits started rolling. That rush to fit in as much information as possible used to be important to me, but now I'm more willing and interested in breaking those rules for the sake of slowing down and taking my time. These days, to make one small painting, I might watch 4 or 5 different things ranging from, say, Agnes Varda's Mur Murs to Steven Spielberg's Jurassic Park to Roberta Cantow's Clotheslines to a slideshow of other people's family photos found at the dump to whatever odd home video shows up when I search for "tee-ball game 1993" or "family vacation 1981" on YouTube. The only thing I require from my source materials is some sense of passing time, a rhythm of movement, a range of vantage points—easy criteria to meet.

With most videos, I watch once, and that's that. But there are a few that I let myself return to over and over again. For the body of work in Overlook, I returned to Les Blank's 1978 documentary Always For Pleasure which features lots of second line parade footage from New Orleans. Also, Kirsten Johnson's 2016 film cameraperson—an autobiographical collage made with footage she shot working as a cinematographer for a dozen disparate documentaries over the course of her decades-long career.

To answer your question about making sketches: No! Never! Not once! These are decidedly planless paintings. I start each one without a sense of where it will go. I try to be as responsive as possible to the footage I'm watching and the painting as it develops, noticing what I notice and trying not to force any formal decisions beyond that. I convince myself that I don't have much control over how these paintings turn out, which makes it easier for me to accept them as they are without too much judgment or scrutiny.

What guides your search for and selection of materials? When you're making a film or billboard collage, to what extent are your decisions driven by the content of your source imagery, versus some external idea, condition or constraint?

AO: It's really fascinating to hear about your process in making the paintings in Overlook! Giving away all your secrets! At least, I wasn't aware of some of the intricacies of the process. It feels extremely generative. It also completely changes the way I view them. I never thought of your oil painting practice through a strictly temporal lens or as a truly—or maybe structurally—time-based process. The way remnants of several films share the same frame feels related to cinematic montage. The paintings also now feel like documentation of their own making under certain constraints and parameters (like the time before the credits roll), rather than a full-throated representation of a thing, which makes me think of the methods of structural filmmakers like Tony Conrad or Lis Rhodes.

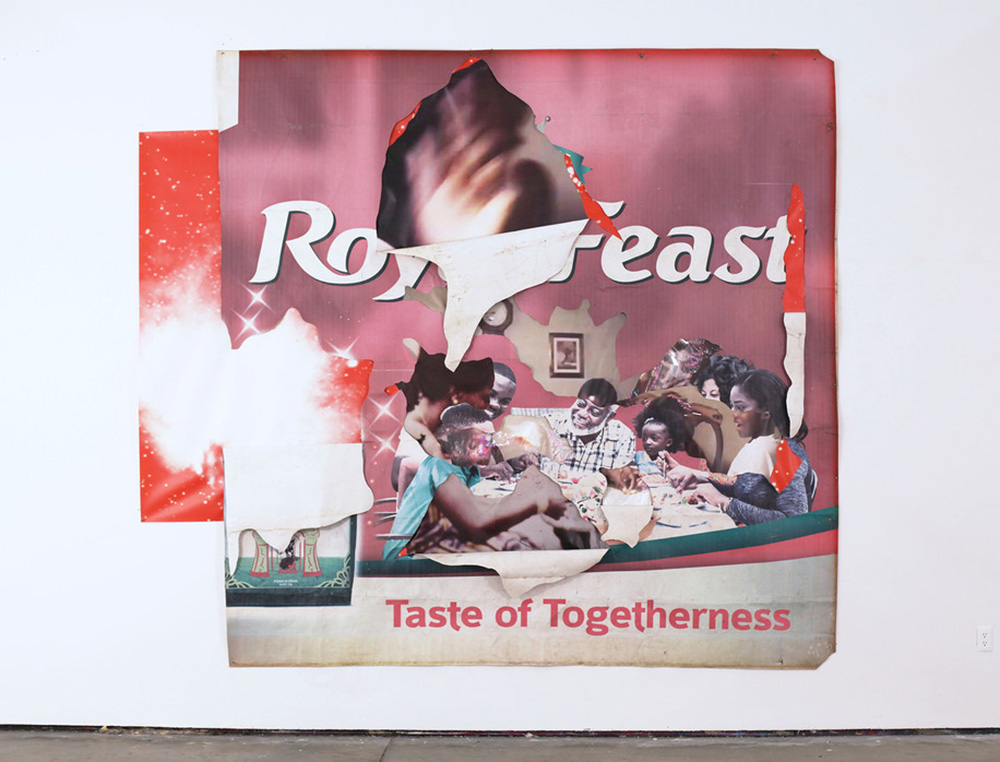

As far as my own process, the search for and selection of materials really depends on what medium I am using. In the end, I don't have any standard criteria for sampling—it's really whatever catches my eye or ear, similar to how you choose color-shapes in frames of film. Several film reels, cassette tapes, advertisements, images, objects, etc. lay around in my studio for months or even years before I figure out what to do with them. My decisions when making a collage (be it moving image, sound, two-dimensional, or three dimensional) are really made in direct conversation with the content of the source itself, and, to borrow a phrase from Arthur Jafa, bring the disparate content from different sources into "affective proximity" to one another. I try to do so without constraints but find myself making several rules for myself along the way.

I'm wondering if you could talk more about control and formal decisions. The paintings all feel like they work compositionally - even though you say that you don't have much control over how they turn out. How do you keep that balance?

![]() Africanus Okokon, Birthday Function, 2019, found vinyl billboard, custom printed vinyl signage, acetate, 126 x 113 inches.

Africanus Okokon, Birthday Function, 2019, found vinyl billboard, custom printed vinyl signage, acetate, 126 x 113 inches.

MC: That "affective proximity" brings me back to José's painting, where a couch, a Dominican Republic pond landscape, and Drake dancing in a yellow puffer jacket (etc.) are all brought close with that looping string/rope compositional device. In your film collages, I realize that your hand-edited film reel is the material loop that brings faraway things together in time and space.

Such a good question regarding formal control. I try to convince myself that the paintings are out of my control, but it's pretty easy to call my own bluff. The compositional structure of each painting and the cohesion of color across the whole show both point to the reality that I do have a firm hold on the reins after all.

For better or for worse, I've developed some painting habits with regard to color-mixing, mark-making, and compositional arrangement. I've also developed some looking habits: when watching all the disparate films, my eye tends to be drawn toward saturated color, toward lighter values, toward small shapes, toward shapes that hug the edges of the frame. I keep returning to parade footage in part because it's filled with all the stuff that suits this sensibility: bright colors, confetti bits, bicycle handles, umbrellas, the long shiny golden loops of trombones cut off by an edge of the frame. I also return to parade footage because it offers me the two kinds of composition that I tend to be looking for: there's the everything-everywhere, loud, busy, colorful composition of a parade in motion; and then there's the sparse, quiet, empty composition of the day after a parade, when all the streamers and confetti have settled on the pavement, scattered, damp and trampled.

There's an important part-two to my response about formal control, but first I want to ask . . . Is there an overarching sensibility that tends to make your work "work"? Some pattern or rhythm that you keep finding yourself looking for or trying to make? A certain type of thing that tends to "catch your eye or ear"? Humble request that you focus a bit on the "ear" part of that question . . . I think so much about volume and rhythm and movement while I'm working, but then make paintings that are by nature silent and still. I'd love to hear more about the role of found music, rhythm, and sound in your film collages.

AO: At the risk of sounding very opaque, sonically, I feel like I'm always searching for that loop. I'm not sure exactly what that means, but I spend hours in the studio listening to my own loops when I'm working and not listening to other people's music. Often when I'm listening to recorded music, I pause it and extract an instrumental or vocal loop and play it for hours while I'm working on something else. Sometimes those loops find their way into artworks and sometimes not. I'm interested in things that might hypnotize you because they are difficult to grasp, things that easily slip through your fingers, like memory itself. They are memories that only exist while they are being mediated. My music taste is pretty all over the place, and my collection holds everything from dub to sunshine pop to noise to techno to highlife to jazz to library music recorded for old educational programs and everything in between. I would say that the music that holds a special place for me is music that sounds like it wasn't supposed to be heard by anyone besides the maker, which is a lot like what I end up making (ha).

Searching for that loop in sound, in my mind, is the same thing as searching for that edit in video, that cut in collage, or that motion in moving images - and I'm thinking a lot about memory and mediation in the process. I'm saying that because "ideal" or "perfect" would be the wrong words; they are never perfect—they are always imperfect—and are always a bit rough and slightly flawed by nature . . . which brings us back to control. What's your "part-two"?

MC: Beautifully put—the never-ending hunt for that loop.

As for my control-themed part-two: there was one big and novel formal decision that I actively made for the body of work in Overlook. In the past, the color world of each painting was dictated by the color world of the film(s) I was watching (so, a black and white film would necessarily yield a black and white painting). For this new body of work, I found my color palette before turning to the film or documentary du jour. I prepped each panel with a color gradient harvested from the sky on my walk to or from my small studio, usually shortly after sunrise and then slightly before sunset.

When I moved to Salt Lake City over the summer, I was so excited to see how the surrounding mountains would change (or appear to change) based on the time of day and also based on the weather. That helped me notice how my thinking and feeling have changed over the past couple of months, largely in response to those same forces. Since moving west, time has passed, seasons have changed, and I find myself thinking differently and feeling lighter. For the first time, I've felt compelled to let my present-tense environment work its way (directly and obviously) into my paintings, in the form of empty spaces filled with color worth feeling curious about.

So, the whole body of work is tied together with these sky-colors, a formal constraint that helped each of these paintings "work," respectively and together. For each panel, I painted a gradient, then pre-mixed a palette with colors related to that gradient. Giving away more secrets . . . ha. I have no secrets! Here's one of my pre-mixed palettes to give you an idea:

![]() snapshot of Capanna’s painting palette, 2021

snapshot of Capanna’s painting palette, 2021

You know, bringing things full-circle, this pre-mixed palette was oddly inspired by our dynamic in Home Vision Test. During our thesis review, critics kept describing our collaboration as "harmonious"—first with happy surprise and then with distrust. There was some real skepticism about the fact that everything in our installation "worked"; that there were no signs of conflict. With this pre-mixed palette, I wondered: what would my paintings look like if I got all the colors to get along with each other first? To agree with one another?

When we de-installed Home Vision Test, you, José, and I agreed (oof, we were all still being agreeable!) that if we worked together again, we might be more willing to step on each other's toes, to disagree, to let dissonance interrupt some of that harmony. Maybe I'll apply that same goal to my next color palette and see what happens.

AO: Seeing your new work really felt like a breath of fresh air, so it makes a lot of sense that you were directly inspired by surroundings that were fresh.

![]()

snapshot of a work by Africanus Okokon in progress, 2021

It's very funny that you, José and I agreed to agree to disagree next time. I think that'd be great.. but I'm not sure if it works like that! Here's a crop of a work-in-progress from my studio with the same color palette as your pre-mixed colors. Even though most of my colors happened by accident… sometimes you can't fight it.

Mariel Capanna (b. 1988, Philadelphia, PA; lives and works in Salt Lake City, UT) received a BFA and Certificate of Fine Art from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and an MFA from Yale University. She has been an artist in residence at the Guapamacátaro Art and Ecology Residency in Michoacan, Mexico; Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture; and at the Tacony Library and Arts Building (LAB) in Philadelphia. Capanna has also been the recipient of the Robert Schoelkopf Memorial Traveling Fellowship and an Independence Foundation Visual Arts Fellowship. Her ongoing project Little Stone, Open Home, with Good Weather is a long-term and perpetually changing fresco in a single-car garage in North Little Rock, Arkansas that serves as a forum for material research and collaboration through public tours, instructional workshops, invitational exhibitions, and community-focused programming. Overlook is her first solo show at Adams and Ollman.

Africanus Okokon (b. 1989, Saint Paul, MN) works with the moving image, performance, painting, assemblage, collage, sound and installation. He received a BFA in Film/Animation/Video from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2013 and an MFA in Painting/Printmaking from Yale University in 2020. He is currently based in New Haven, CT.

![]()

Mariel, José and Africanus, 2020

Photo: Dawn Kim

1Last February, friends and classmates Mariel Capanna, Africanus Okokon, and José de Jesus Rodriguez decided to use the Yale 2020 Painting & Printmaking Thesis show as an opportunity to co-author a collaborative project, rather than to present solo work. This experiment in collective decision-making yielded Home Vision Test: an installation of multiple perspectives.

![]() Mariel Capanna, José de Jesus Rodriguez, Africanus Okokon, Home Vision Test, 2020, Yale School of Art.

Mariel Capanna, José de Jesus Rodriguez, Africanus Okokon, Home Vision Test, 2020, Yale School of Art.

As far as my own process, the search for and selection of materials really depends on what medium I am using. In the end, I don't have any standard criteria for sampling—it's really whatever catches my eye or ear, similar to how you choose color-shapes in frames of film. Several film reels, cassette tapes, advertisements, images, objects, etc. lay around in my studio for months or even years before I figure out what to do with them. My decisions when making a collage (be it moving image, sound, two-dimensional, or three dimensional) are really made in direct conversation with the content of the source itself, and, to borrow a phrase from Arthur Jafa, bring the disparate content from different sources into "affective proximity" to one another. I try to do so without constraints but find myself making several rules for myself along the way.

I'm wondering if you could talk more about control and formal decisions. The paintings all feel like they work compositionally - even though you say that you don't have much control over how they turn out. How do you keep that balance?

Africanus Okokon, Birthday Function, 2019, found vinyl billboard, custom printed vinyl signage, acetate, 126 x 113 inches.

Africanus Okokon, Birthday Function, 2019, found vinyl billboard, custom printed vinyl signage, acetate, 126 x 113 inches.MC: That "affective proximity" brings me back to José's painting, where a couch, a Dominican Republic pond landscape, and Drake dancing in a yellow puffer jacket (etc.) are all brought close with that looping string/rope compositional device. In your film collages, I realize that your hand-edited film reel is the material loop that brings faraway things together in time and space.

Such a good question regarding formal control. I try to convince myself that the paintings are out of my control, but it's pretty easy to call my own bluff. The compositional structure of each painting and the cohesion of color across the whole show both point to the reality that I do have a firm hold on the reins after all.

For better or for worse, I've developed some painting habits with regard to color-mixing, mark-making, and compositional arrangement. I've also developed some looking habits: when watching all the disparate films, my eye tends to be drawn toward saturated color, toward lighter values, toward small shapes, toward shapes that hug the edges of the frame. I keep returning to parade footage in part because it's filled with all the stuff that suits this sensibility: bright colors, confetti bits, bicycle handles, umbrellas, the long shiny golden loops of trombones cut off by an edge of the frame. I also return to parade footage because it offers me the two kinds of composition that I tend to be looking for: there's the everything-everywhere, loud, busy, colorful composition of a parade in motion; and then there's the sparse, quiet, empty composition of the day after a parade, when all the streamers and confetti have settled on the pavement, scattered, damp and trampled.

There's an important part-two to my response about formal control, but first I want to ask . . . Is there an overarching sensibility that tends to make your work "work"? Some pattern or rhythm that you keep finding yourself looking for or trying to make? A certain type of thing that tends to "catch your eye or ear"? Humble request that you focus a bit on the "ear" part of that question . . . I think so much about volume and rhythm and movement while I'm working, but then make paintings that are by nature silent and still. I'd love to hear more about the role of found music, rhythm, and sound in your film collages.

AO: At the risk of sounding very opaque, sonically, I feel like I'm always searching for that loop. I'm not sure exactly what that means, but I spend hours in the studio listening to my own loops when I'm working and not listening to other people's music. Often when I'm listening to recorded music, I pause it and extract an instrumental or vocal loop and play it for hours while I'm working on something else. Sometimes those loops find their way into artworks and sometimes not. I'm interested in things that might hypnotize you because they are difficult to grasp, things that easily slip through your fingers, like memory itself. They are memories that only exist while they are being mediated. My music taste is pretty all over the place, and my collection holds everything from dub to sunshine pop to noise to techno to highlife to jazz to library music recorded for old educational programs and everything in between. I would say that the music that holds a special place for me is music that sounds like it wasn't supposed to be heard by anyone besides the maker, which is a lot like what I end up making (ha).

Searching for that loop in sound, in my mind, is the same thing as searching for that edit in video, that cut in collage, or that motion in moving images - and I'm thinking a lot about memory and mediation in the process. I'm saying that because "ideal" or "perfect" would be the wrong words; they are never perfect—they are always imperfect—and are always a bit rough and slightly flawed by nature . . . which brings us back to control. What's your "part-two"?

MC: Beautifully put—the never-ending hunt for that loop.

As for my control-themed part-two: there was one big and novel formal decision that I actively made for the body of work in Overlook. In the past, the color world of each painting was dictated by the color world of the film(s) I was watching (so, a black and white film would necessarily yield a black and white painting). For this new body of work, I found my color palette before turning to the film or documentary du jour. I prepped each panel with a color gradient harvested from the sky on my walk to or from my small studio, usually shortly after sunrise and then slightly before sunset.

When I moved to Salt Lake City over the summer, I was so excited to see how the surrounding mountains would change (or appear to change) based on the time of day and also based on the weather. That helped me notice how my thinking and feeling have changed over the past couple of months, largely in response to those same forces. Since moving west, time has passed, seasons have changed, and I find myself thinking differently and feeling lighter. For the first time, I've felt compelled to let my present-tense environment work its way (directly and obviously) into my paintings, in the form of empty spaces filled with color worth feeling curious about.

So, the whole body of work is tied together with these sky-colors, a formal constraint that helped each of these paintings "work," respectively and together. For each panel, I painted a gradient, then pre-mixed a palette with colors related to that gradient. Giving away more secrets . . . ha. I have no secrets! Here's one of my pre-mixed palettes to give you an idea:

snapshot of Capanna’s painting palette, 2021

snapshot of Capanna’s painting palette, 2021You know, bringing things full-circle, this pre-mixed palette was oddly inspired by our dynamic in Home Vision Test. During our thesis review, critics kept describing our collaboration as "harmonious"—first with happy surprise and then with distrust. There was some real skepticism about the fact that everything in our installation "worked"; that there were no signs of conflict. With this pre-mixed palette, I wondered: what would my paintings look like if I got all the colors to get along with each other first? To agree with one another?

When we de-installed Home Vision Test, you, José, and I agreed (oof, we were all still being agreeable!) that if we worked together again, we might be more willing to step on each other's toes, to disagree, to let dissonance interrupt some of that harmony. Maybe I'll apply that same goal to my next color palette and see what happens.

AO: Seeing your new work really felt like a breath of fresh air, so it makes a lot of sense that you were directly inspired by surroundings that were fresh.

snapshot of a work by Africanus Okokon in progress, 2021

It's very funny that you, José and I agreed to agree to disagree next time. I think that'd be great.. but I'm not sure if it works like that! Here's a crop of a work-in-progress from my studio with the same color palette as your pre-mixed colors. Even though most of my colors happened by accident… sometimes you can't fight it.

Mariel Capanna (b. 1988, Philadelphia, PA; lives and works in Salt Lake City, UT) received a BFA and Certificate of Fine Art from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and an MFA from Yale University. She has been an artist in residence at the Guapamacátaro Art and Ecology Residency in Michoacan, Mexico; Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture; and at the Tacony Library and Arts Building (LAB) in Philadelphia. Capanna has also been the recipient of the Robert Schoelkopf Memorial Traveling Fellowship and an Independence Foundation Visual Arts Fellowship. Her ongoing project Little Stone, Open Home, with Good Weather is a long-term and perpetually changing fresco in a single-car garage in North Little Rock, Arkansas that serves as a forum for material research and collaboration through public tours, instructional workshops, invitational exhibitions, and community-focused programming. Overlook is her first solo show at Adams and Ollman.

Africanus Okokon (b. 1989, Saint Paul, MN) works with the moving image, performance, painting, assemblage, collage, sound and installation. He received a BFA in Film/Animation/Video from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2013 and an MFA in Painting/Printmaking from Yale University in 2020. He is currently based in New Haven, CT.

Mariel, José and Africanus, 2020

Photo: Dawn Kim

1Last February, friends and classmates Mariel Capanna, Africanus Okokon, and José de Jesus Rodriguez decided to use the Yale 2020 Painting & Printmaking Thesis show as an opportunity to co-author a collaborative project, rather than to present solo work. This experiment in collective decision-making yielded Home Vision Test: an installation of multiple perspectives.

Mariel Capanna, José de Jesus Rodriguez, Africanus Okokon, Home Vision Test, 2020, Yale School of Art.

Mariel Capanna, José de Jesus Rodriguez, Africanus Okokon, Home Vision Test, 2020, Yale School of Art.